Korda Marshall harbours two distinct, sometimes warring, personalities.

First, there’s the A&R extraordinaire with an independent heart; the owner of – as the industry adage would have it – ‘great ears’, who discovered Muse, Ash, Alt-J, Garbage and The Temper Trap before anyone else had a sniff.

And then there’s the business-savvy mogul; the guy who became a wheeler-dealer by selling home-grown vegetables in his early teens – and who grafted his way up the greasy pole of not one but two major labels in RCA and Warner Bros. (Before getting kicked out of both.)

And then there’s the business-savvy mogul; the guy who became a wheeler-dealer by selling home-grown vegetables in his early teens – and who grafted his way up the greasy pole of not one but two major labels in RCA and Warner Bros. (Before getting kicked out of both.)

These two vying elements to Marshall’s make-up – the creative and the commercial; the poetic and the profiteering – have been the bedrock of his latest great success, Infectious “mk. 2”.

Back in 1998, Marshall sold his original Infectious Records to Rupert Murdoch’s News International. It was eventually swallowed into Warner Music Group and looked gone forever.

But in 2009, fresh from a successful eight -year run at Atlantic/Warner, Marshall re-started Infectious as an independent, signing The Temper Trap – and their global mega-hit Sweet Disposition.

His career has seen him climb to two very senior positions at the majors: Head Of A&R at RCA in the early ‘90s and MD of Warner Bros Records in the early noughties. Both times, his rebellious side – his independent side? – won out and he was, as he gently puts it, “summarily dismissed”.

Having built Infectious Mk. 2 to worldwide recognition with a roster including The Temper Trap, These New Puritans, Local Natives, Superfood, Drenge (pictured), The Acid and, of course, Alt-J, Marshall last year sold the business to BMG.

He now operates within the Bertelsmann-owned company, still running Infectious but also directing traffic at the company’s artist services record business.

As such, acts he’s currently working with include his much-loved Drenge and Alt-J, as well as BMG acts The Charlatans, Jack Savoretti, You Me At Six, Bryan Ferry and Leftfield.

Way before any of this, though, was the wide-eyed, romantic Korda – the one stood aged 12 in the audience at Earls’ Court being blown away by David Bowie; and the one who would go on to become a reasonably successful drummer in his own right with two bands, The Thin Men and Zerra One.

Way before any of this, though, was the wide-eyed, romantic Korda – the one stood aged 12 in the audience at Earls’ Court being blown away by David Bowie; and the one who would go on to become a reasonably successful drummer in his own right with two bands, The Thin Men and Zerra One.

It’s this guy who shines through when he talks about new Infectious signings like The DMA’s – an Aussie three-piece he enthusiastically defines as “every great Mancunian band you’ve ever heard rolled into one”.

Behind this giddy excitement, though, always lurks the canny deal-maker, ready to do battle toe-to-toe with those who would see his beloved artists stolen away – or, even worse, fail altogether.

[PIAS]’s Kenny Gates sat down with Marshall to get a picture of a very businesslike independent music hero.

Korda, how are you?

I’m very well – I’m excited about doing this interview. From one icon to another!

Do you remember the first time we met? My recollection was that it was in Cologne at Popkomm. You came storming after me – “Ash, Ash, Ash, Ash…” I realised this guy is either a passionate music lover or a crazy man!

You’re not alone. A few people have wondered that – including my missus….

Why did you end up working in music?

I grew up in a world of craftsman and designers surrounded by creative people. My dad ran something called the Design Council in the ‘60s and we lived in a very crazy arty house in West London. I grew up in the world of [famed potters] Janet Leach and Bernard Leach and all these great designers.

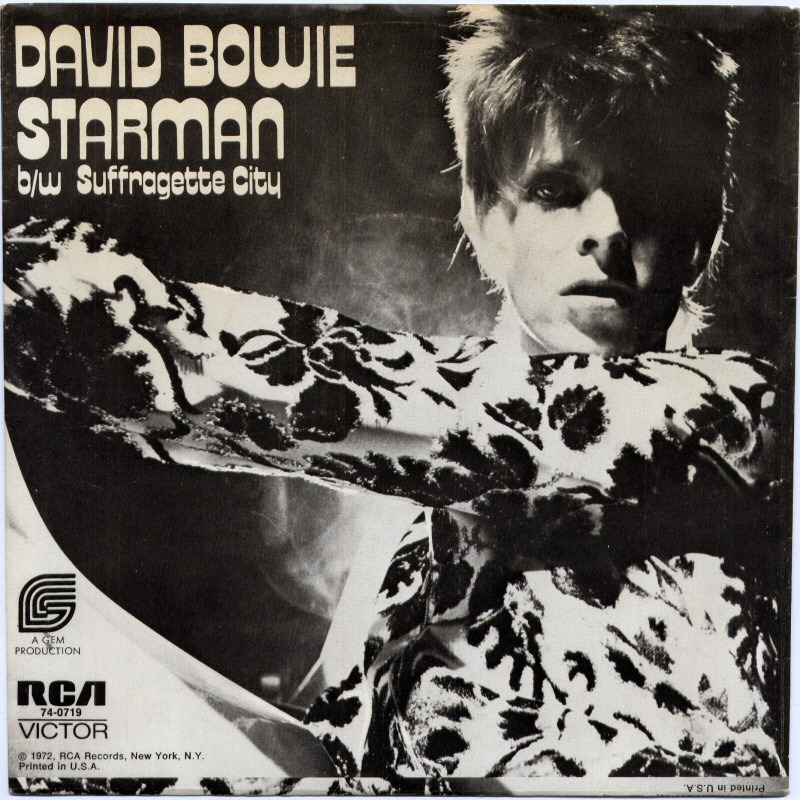

I remember seeing David Bowie play Starman on Top Of The Pops – I’d have been 12. This androgynous figure amazed me; I fell in love. The Rise & Fall Of Ziggy Stardust was the first album I bought.

Any other influences from your childhood?

My elder sister had a boyfriend who was Deep Purple’s tour manager at the time. He told me about Bowie playing Earls’ Court, so I saw him there when I was 12 and I saw the last ever Ziggy Stardust show when I was 13 at Hammersmith.

My elder sister had a boyfriend who was Deep Purple’s tour manager at the time. He told me about Bowie playing Earls’ Court, so I saw him there when I was 12 and I saw the last ever Ziggy Stardust show when I was 13 at Hammersmith.

The very next week, my parents moved us down to Cornwall, in a little village called Roche – eight miles from the nearest town. I had no friends, a cockney accent… I felt ostracised.

I subscribed to the NME, Sounds and Melody Maker and bought a drum kit. I used to grow vegetables in the garden and sell them at the local market to raise enough money to get the bus into town and buy as many records as I could.

What was your first job in music?

I left Cornwall when I was 18 and went to Canterbury Art College to study architecture. I didn’t actually want to be an architect, but I knew Pink Floyd were all architects.

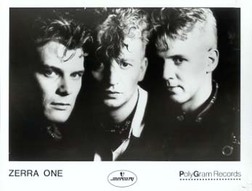

When I was at Canterbury, I joined a local art school band called The Thin Men and we became a big fish in a little pond. Then we did some Radio 1 sessions and what have you. After we split up I joined another band called Zerra One, which was my first real engagement with the music business.

“I wrote 256 letters to people in the music industry. There were eight replies.”

They were a three-piece and they needed a drummer. At that time I could play a drum solo and roll a joint at the same time – I was a terrible drummer, but that trick got me the job. Because I bought an electronic drumkit, it meant we could get all the equipment in the back of hatchback, so we could make £50 support gigs work. That also weighed in my favour.

We toured with Echo & The Bunnymen, The Cure, Peter Gabriel – we did loads. I walked out of that band in the middle of the Peter Gabriel tour in Newcastle – ‘creative differences’ – and decided to see if I could get in to the music business proper.

I wrote 256 letters to publishers, agents, record companies, managers. There were eight replies. One of them was a phone call from a guy called Peter Robinson [at RCA] who said he was looking for a scout. I had nine hours of interviews and eventually got offered a job for £20 a week with bus pass and luncheon vouchers in January 1983. I was No.9 in a department of eight in RCA A&R. My job was coffee maker, tape copier, dogsbody.

What came next?

I discovered The Blow Monkeys. We went to New York and got Michael Baker to re-record their songs, and we mixed a track called Digging Your Scene which was a big hit. That impressed the bosses and I got to have a proper job in A&R.

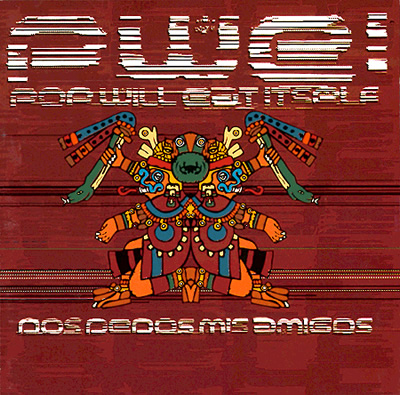

From there I ended up working with a band called Londonbeat with Dave Stewart and signed The Wedding Present, The Primitives and Pop Will Eat Itself

I then became a Senior A&R Manager looking after bands including The Silencers – who sold a lot of records in France – and Curve, who by that point had broken through.

Then in 1988 I was made Head of A&R for three years, and then in 1991, I helped to sign M-People and Take That.

Take That? I think I’ve heard of them.

Did you know I got fired for signing Take That? I signed them with Nick Raymonde, who was the A&R manager, then it all went wrong. And then, when it all went right, Nick got the credit and all the royalties! He’s a lovely man but I got summarily walked out of the building by the new regime after 10 years at RCA.

“The new regime decided they didn’t like what they saw. I got a bullet for spending too much on take that.”

The new regime came into the company, took a look at it all and decided they didn’t like what they saw and I was responsible. I got a bullet for spending too much money on Take That. I had a three year firm deal, luckily, so I walked out with two-and-a-half-years salary.

Let me guess – that money started Infectious?

Exactly. I started Infectious on April 27th 1993. After my face didn’t fit with the new regime at RCA, I was arrogant enough to think I’d just walk into a new job.

Exactly. I started Infectious on April 27th 1993. After my face didn’t fit with the new regime at RCA, I was arrogant enough to think I’d just walk into a new job.

I remember sitting in a hammock in the garden and my second child, William, had just been born. It was the beginning of mobile telephones, phones on cables, so I could sit in the garden with a notepad, telephone and a boogie box with a cassette player. That’s how Infectious started.

The first act I signed to Infectious was Pop Will Eat Itself, which we signed for £5k because that was all I had in the bank account. That album [Dos Didos Mis Amigos, pictured] did about 60,000 sales so in a very short space of time I had a proper business. I later sold half of Infectious to Michael Gudinski [Mushroom Records founder].

We rolled it all together and then signed Ash at 15 years old – for £12k – Muse at 17 years old, Paul Oakenfold, Peter Andre, Garbage. We went from nowhere to being a £5m-a-year business in five years and I have a lot to thank Michael for.

You then sold Infectious completely, right?

Yes, in 1998 we sold the business to James Murdoch.

I remember it – we lost the licence!

Sorry about that! We all made a lot of money – there was a lot of it swimming around in 1998 – and James Murdoch became my boss. Then I tried to do an MBO, which didn’t work, so we brokered a deal with Roger Ames for Warner to buy Mushroom.

Then when I eventually left Warner in spring ’09, I started Infectious Mk.2 – totally independent with private money.

The last six years of Infectious has just been about music and artists I adore. BMG bought the business last autumn and now I’m running BMG’s frontline records business.

What we’re trying to do there is carve out a space between the independent labels and the major labels: it’s a well-financed European corporation that looks after and treats its acts as if it was an independent.

So you were major, then independent, then independent funded by a corporation, then back into a major with eight years at Warner, then an independent again. So are you an independent or a major?!

I’m an independent! I was thrown out of Warners. There was masses of politics.

Politics that saw Max Lousada somehow squeeze you out?!

[Laughs]. I love Max, I trained Max. He’s a beautiful man. We signed The Darkness and James Blunt together. He’s well trained!

And you left The Darkness’s distribution with [PIAS]…

I got into so much trouble for that. But I assume you made a nice few quid.

I remember having the conversation with Ames: “We’ve got to leave The Darkness with [PIAS]. They’ve been on board since the start and now it’s exploding.”

What’s the difference between an indie and a major, then?

Philosophically, there’s a huge difference. At most major labels, the top 5% of the company worldwide all have the understanding that the artists are working for them. At independents, the executives work for the artists. At BMG we work for the artists.

“At majors, the top 5% of the company understand the artists work for them. At independents, the executives work for the artists.”

I ask this of everyone: are you a hopeless romantic?

Yeah, of course ask my missus but I’m a businessman as well. If you’re going to grow apples, you’ve got to prune some trees. There was a day when I had to sit down and fire 17 people one afternoon at Warners. That was one of the key factors for why I didn’t try and re-negotiate [my contract] at Warners. Keeping the human side is important.

Which music executives have you most respected in your career?

Well there’s the old ones and the new ones. What Geoff Travis did, what Daniel Miller did and what Laurence has done at Domino – I admire them all. But more than anyone else, it’s Richard Russell at XL. I’ve always wanted to be him when I grow up. He’s a genius.

Then in the major world, I grew up with Mo Ostin, Lenny Waronker and I had the pleasure of meeting Ahmet Ertegun. I was also told off a few times and trained by Clive Davis; Clive told me that music decisions should be made by music people, not lawyers or accountants.

In the modern world I admire people like Steve Ralbovsky – he’s got Alt-J in America and I take a lot of pleasure working with him.

What about Michael Gudinski?

Gudinski taught me an awful lot about hustling, about how to run a business, international deals, building a company and working with artists. He was my consigliere for ten years and a genius in his own way.

Dave Stewart taught me about working with artists too. I remember being in the studio and him saying he wanted [the sound] to be “more orange”.

What are your proudest moments in music – and your lowest moments?

My proudest moments are my three beautiful children and meeting my beautiful wife Tracy.

My proudest business moment was when I first walked out of RCA with a huge cheque in 1993, and then the second one was when I sold Infectious to Murdoch for north of a million quid in 1998.

“Dave Stewart taught me about working with artists. I remember him saying in the studio, ‘It needs to sound more orange’.”

My third proudest was selling Infectious to BMG for, er, for…

… for more than ten quid.

… for more than ten quid, thank you. Musically, which is much more exciting, my proudest moments would obviously include [The Blow Monkeys’] Digging Your Scene because that was my first proper hit record.

… for more than ten quid, thank you. Musically, which is much more exciting, my proudest moments would obviously include [The Blow Monkeys’] Digging Your Scene because that was my first proper hit record.

Independently, there was the summer when I had three hits all with ‘girl’ in the title: Girl From Mars by Ash, Mysterious Girl by Peter Andre and Stupid Girl by Garbage (pictured). Obviously, Muse and Alt-J, I’m very proud of both of those.

And after I left Warners, I signed a beautiful Australian act called Temper Trap whose song Sweet Disposition grew Infectious Mk.2 from nowhere to a £2m turnover in its first nine months.

I still have the licence of Sweet Disposition so I know that story well! I remember hearing: ‘Korda’s back.’ Okay, let’s see… And then your first act just explodes. How many syncs of that record have there been now?

Hundreds. It’s one of the most synched records of the past decade. I did what Daniel Miller did with the Moby album [Play] – I had a lot of money involved and thought, I can’t just rely on radio.

My kids dragged me to see The Temper Trap in some dodgy club. By the second song, the lead singer, Dougie, walked on with a little green beanie hat on and started singing Sweet Disposition – and the voice of an angel came out. It was a no-brainer. I started Infectious because I found the band. I was supposed to be going sailing!

Gudinski rang me and said: ‘Do you want it?’ I wasn’t sober, but I said yes. And Infectious version two was born.

And then I came to see [PIAS] who gave us a distribution deal, and we were on our way. And, by the way, it wouldn’t have been the success it has been on any other company than [PIAS].

Thank you. Are you going to avoid telling me your lowest moment because you’re too much of an optimist?

[Laughs]. No, I’ve had a few. Spending £300,000 on a video with Malcolm McLaren – on an act I won’t mention – was pretty horrendous. Sitting down and firing those 17 people at Warner Bros was obviously horrible. And getting fired at RCA first time round was pretty low; there’s nothing worse than being thrown out of a building by a security guard after ten years. That’s pretty heavy.

You’ve mentioned your kids. Two of the three are the business, correct?

Yep, one of them is still at university. Summer is a very successful agent at CAA now – she was on my knee when we sat in the studio and listened to Garbage’s Stupid Girl. She was [side] of the stage with Ash at Reading when she was seven. We used to buy her albums every week. She works with Mike [Greek] and Emma [Banks] at CAA – together they look after Sam Smith, Paloma Faith and others.

William graduated in architecture and has just started at Metropolis as a junior promoter. Nothing to do with me; they both got their jobs independently.

“There’s nothing worse than being thrown out of an office by a security guard after ten years. That’s pretty heavy.”

Summer brought me The Darkness when she was about 16 – she has great ears, always has done. She also came to me and said: “That You’re Beautiful song by that James Blunt guy could really work.”

I’d have A&R meetings at Warner or Mushroom on the Friday. Then on Sunday mornings I’d cook Sunday lunch at home and play all the music that had sifted to the top to my kids. They were much more brutal than the professionals.

As an A&R man, you have a strong self-belief – your record shows it, especially when you’re spending your own money. But how do you manage those moments of insecurity when you look in the mirror and think: ‘I’ve gone all in on this band.’

Well, I felt alienation I felt when I was loving David Bowie in the early ‘70s in West London surrounded by skinheads, and I felt alienation when I was taken off to Cornwall by my parents in my flared jeans and Afghan coat.

I learnt through those periods that it’s a very fine line between confidence and arrogance. I abhor arrogance; it’s a very nasty, dark influence.

I learnt that the process of self-belief from my dad and the creative people I was around in Cornwall. As an artist, if you’re making decisions about enameling, pottering, painting, designing a ring, you have to be confident in what you’re making.

Ultimately in A&R, you can’t convince other people to believe if you don’t believe yourself. So sometimes you have to go into a false self-prophesying mode that says ‘this is great, we’re going to do this’ – if you can believe it strong enough, you can make it happen.

In all of your career, in all of your signings, is there one artist that you’re most proud of?

There’s a few. I’m incredibly proud of Garbage. Shirley Manson is a genius. I first met her when she was 15, this bolshy, cocky little redhead in Edinburgh.

There’s a few. I’m incredibly proud of Garbage. Shirley Manson is a genius. I first met her when she was 15, this bolshy, cocky little redhead in Edinburgh.

She was the backing singer in Goodbye Mr. Mackenzie. I flew up to see them. I didn’t sign the band but she was great. Butch Vig, what a producer. Then there’s Muse (pictured) – Matt Bellamy’s amazing.

I remember you telling me: ‘Muse are the next Queen’.

That’s true. I first saw Queen at Plymouth Guildhall when I was 15. I couldn’t afford the ticket so I bought 30, hired a coach and then sold the [ticket and travel package] so I could afford to go. I grew up loving Queen, those first two albums are amazing.

When I first saw Muse, he had this amazing voice, and if you shut your eyes with that falsetto voice, there’s Freddie.

You recently said Infectious was your personal soundtrack to Blade Runner. Does that mean Infectious is an eighties label?

[Laughs] Very good! As an entrepreneur, I like to create self-professed parameters. If you try and do everything you’ll never succeed. True story: at Mushroom, I had a very strict rule that we would not sign anybody over 21 or under 30. I didn’t want to deal with stroppy 27-year-old guitarists.

I won’t go too far into Atlantic and Warner, but Atlantic [signings] were based on [the ability to sell] 15 million albums worldwide – let’s say there were a lot of helium balloons!

The Infectious mantra, which goes back to seeing The Temper Trap, is what would happen if we walked out of the little yellow taxi with the dummy driving it in Blade Runner; what would a record label look like?

“When we started infectious mk.2 I wanted it to be totally digital, no physical at all. In the end we probably ended up more logan’s run than blade runner!”

Initially, I didn’t want an office with Infectious – I wanted it all done over Skype and to be totally digital, no physical stock at all. In the end, that didn’t quite happen – we probably ended up more Logan’s Run than Blade Runner!

If you listen to all the music on Infectious mk.2 , it all belongs on my personal imaginary Blade Runner soundtrack: the floaty atmospherics of Sweet Disposition, the futuristic melody of Alt-J, the harmonies of Local Natives, the orchestral four-piece, diva-esque style of These New Puritans.

I hear the new Leftfield album is getting you excited…

Oh yes. It’s a brilliant record. At BMG I want to bring the whole thing together. There was a roster here [at BMG] when we came in, so we’ve put them together and we’ve now got an amazing collection of artists: Bryan Ferry, You Me At Six, Charlatans, Leftfield, Aqualung, Alt-J, Drenge, The Acid, Temper Trap and we’re hoping to work with James and Local Natives.

We’ve also signed two great new acts; The DMA’s from Australia, who sound like every great Mancunian band you’ve ever heard rolled into one, and a great young rock act called We Are The Ocean.

Do you have a special anecdote you can share with us from your career?

Oh, I’m rubbish at anecdotes. I can say I’ve made every mistake in the book; I’ve flown to Edinburgh when I should have flown to Glasgow to see bands; I’ve flown to Berlin to see a band and been too late; I’ve lost entire album master tapes for months and then found them under my desk; I took £5k in tour cash once, put it in my jacket pocket and left it on the plane.

And I’m proud of every single error, because I’ve never made the same mistake twice.