Ever since Steve Lamacq landed a permanent gig on the Radio 1 Evening Session in 1993, he’s been introducing the UK to joyful, challenging, effervescent and era-defining new music.

Along the way, he’s played a key role in breaking a few bands you might have heard of; you know, Coldplay, Oasis, Blur, Pulp, Arctic Monkeys – all the small ones.

Pin him down on who the most exciting band in the world is right now, and he might tell you it’s Bristol punks IDLES or acclaimed Dead Oceans signings, Shame – and he’ll talk about both with every bit as much enthusiasm and energy as he once did Messrs Martin, Gallagher and Albarn.

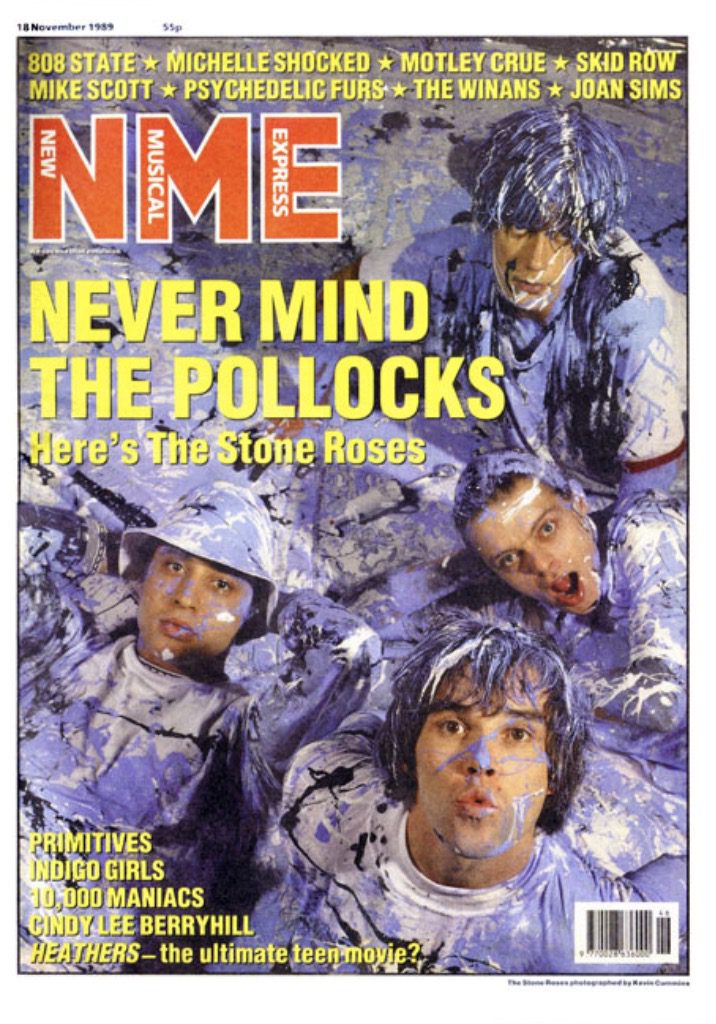

That’s because every day of Steve Lamacq’s career – from pirate radio, to a stint on the NME, to 16 years on BBC Radio 1 and his current daytime show on 6Music – has been dedicated to discovering and sharing amazing things that you’ve never heard before.

As he explains to [PIAS]’s Kenny Gates below, Lamacq’s fixation on the obscure and uncharted is a little bit to do with the fact he’s a born show-off (his words, not ours).

But mainly, it’s because – like John Peel before him – Lamacq believes that if you’re great, you deserve to be heard.

And if no-one else is giving you a leg-up to stardom, he may as well do it himself…

What was your upbringing like and how did you first form a relationship with music?

What was your upbringing like and how did you first form a relationship with music?

I grew up in a very small village in Essex, around 50 or 60 miles from London. At the last census the population of the village was 1,003. It’s got a village green, a pub, a church… and that’s it. It was an idyllic place to grow up, but there weren’t many kids my age there. Being an only child, you end up making your own entertainment, and my entertainment was music.

I can’t remember how it came to be that I suddenly fell in love with pop music. But one week, listening to the Top 20 – as it was – on Radio 1, I started becoming fascinated by these songs and who made them. I bought my first single, which was Tiger Feet by Mud – No.1 in 1974 – and that’s how it started. Within a few months, I’d stopped buying comics and I’d started buying a music paper called the Record Mirror.

Radio 1 was the reason you started listening to music in the first place?

Radio 1 was the reason you started listening to music in the first place?

Yeah, daytime Radio 1. At that age you only know the pop charts – they played all the new releases. I then moved to a bigger school, and I remember in an art lesson, our teacher, Miss Jones, said: ‘Today children, I’d like you to draw what you want to be when you grow up.’ And I drew a bloke and two record players in what I imagined a radio studio would look like.

Miss Jones came round and said, ‘What’s this?’ So I told her it was a DJ on the radio, and that’s what I wanted to be when I grow up. And she said, ‘Oh, you’ll grow out of it.’ Turns out I never did.

Well… I sort of did because pop music went rubbish in 1976 and I lost all faith in it. And then you do what boys of aged 12 do, which is obsess about football instead. But then when you start being given homework at big school, you end up in your bedroom, and so I started turning the radio back on.

In late 1977 I heard a song called Do Anything You Wanna Do by Eddie & The Hot Rods, and I thought: ‘This is magnificent.’ That and 2-4-6-8 Motorway by the Tom Robinson Band [meant] I fell straight back in love with pop music again. 1978 into 1979 was a great era for pop music.

Depeche Mode, Fad Gadget…

Yeah, everything you would find on John Peel’s programme. By accident my dad was playing around with the radio just before I went to bed one night, and it was just at the start of the John Peel [show], and all I heard was the introduction: ‘Tonight on the programme we’ll have music from Fad Gadget, Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark and something from Siouxsie and The Banshees.’ I thought: ‘Who are these people?! They sound amazing!’

“I thought: ‘Who are these people?! They sound amazing!’”

So I went upstairs, as a lot of us did at the time, with a little transistor radio and an earpiece and started listening to John Peel. Every week, music seemed to be progressing. The first wave of punk seemed to [evolve] into Magazine, and then into the indie labels… you got Silicon Teens, Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark’s first single on Factory, even people like Adam And The Ants were good for a while.

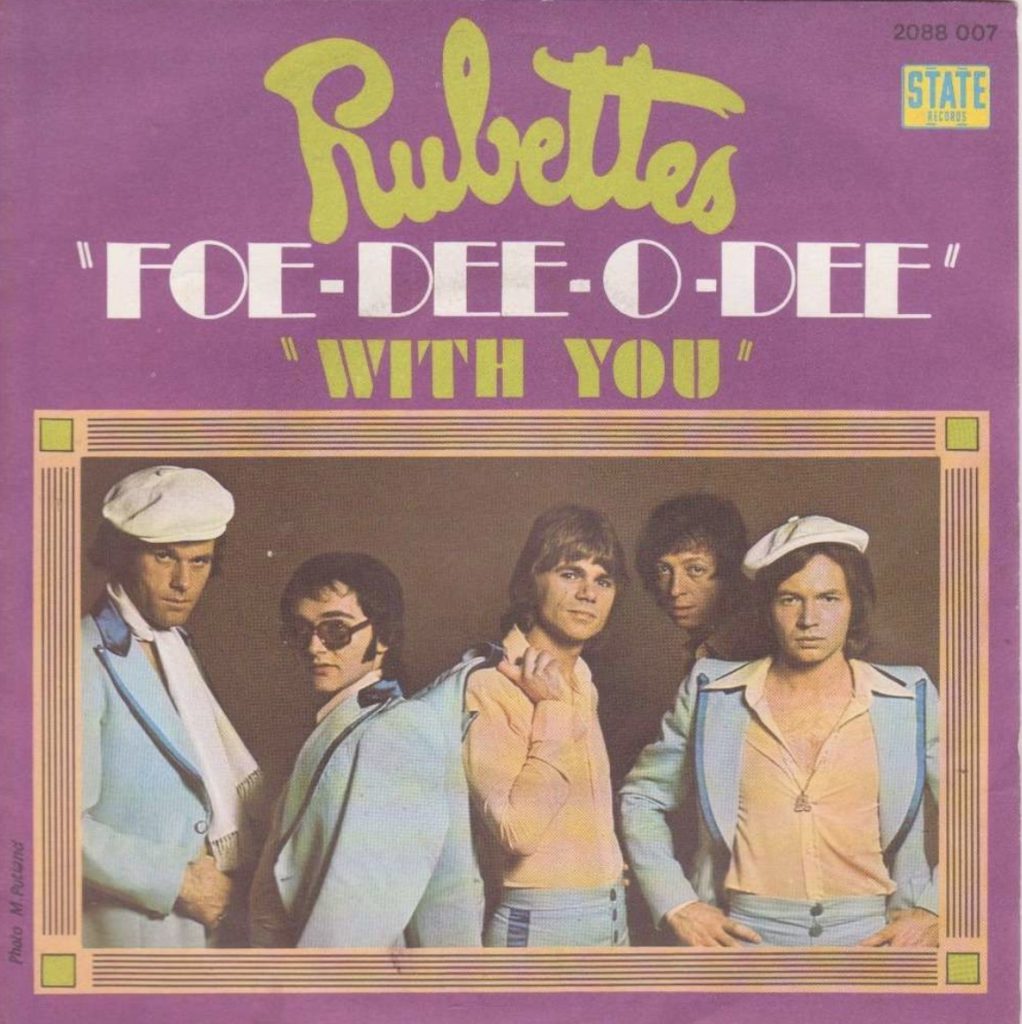

The first thing I bought was The Rubettes – Foe-Dee-Oh-Dee. I’m not really proud of it, but at the time I thought it was amazing…

The first thing I bought was The Rubettes – Foe-Dee-Oh-Dee. I’m not really proud of it, but at the time I thought it was amazing…

There’s a brilliant story about The Rubettes. You remember they used to wear white, with a white beret? I was told once that [the label] had signed The Rubettes, and obviously in those days you had to have an image – like Mud, Slade and Sweet.

They called a big meeting at the record label, with marketing, A&R and everyone in it, and they say: ‘What are we going to do with The Rubettes?’ The secretary of the boss of the company comes in and says, ‘Do you want any coffee?’ And then, ‘If there’s nothing else, I’ll nip out for lunch.’

All these people are sat in the room trying to work out what The Rubettes should look like.

She comes in from her lunch break and the boss of the company says, ‘What have you just bought?’ And she takes out from her bag… a white beret, puts it on, and everyone in the room goes… That’s The Rubettes!

Did your parents encourage you to be a DJ? Or did they want you to be a doctor, lawyer or engineer?

I wasn’t really pressured into doing anything. When I got to about 16 I looked around where I was growing up, looked at Radio 1, and thought, ‘There’s no way someone who grows up here, ends up [there]…’

I was quite interested in writing, so by the time I got to Sixth Form I started a fanzine and that then led to a career in music journalism. I studied journalism at college, then got a job on the local newspaper, and then went on to the NME.

I’d kind of given up on the idea of being a DJ until, when I was working at the NME, I got a phone call from a guy called Sammy Jacob, who was running a pirate [radio] station called Q102. I wrote a piece about Q102, and two weeks later Sammy said, ‘You’ve got quite a good voice, do you fancy doing a show?’ I did two years on Q102, ad that’s how I got back into it.

Where were you buying your records?

All over the place. When I was growing up, I’d go into Colchester – 10 miles away – where there was a record shop called Parrot Records. People forget that we used to go to record shops not just to buy records – it was sort of central to the music community.

“You could stand there for 10 minutes just looking at people’s shoes.”

You’d go in and look at all the new releases, which would take about 15 minutes, but you’d stay in the shop for an hour and a half just looking at people as they came in, overhearing conversations about what they were buying and why they were buying it. In one corner, there’d be all the ‘musicians wanted’ adverts, flyers for the gigs. You could stand there for 10 minutes just looking at people’s shoes. You learnt so much just standing in a record shop, which we’ve lost to a certain extent now.

How did you get to the BBC from pirate radio? And how did you feel when you first got to the BBC?

How did you get to the BBC from pirate radio? And how did you feel when you first got to the BBC?

It was frightening. Just before I resigned from the NME, there were some changes going on at Radio 1, where I’d made one or two friends on the outskirts. A producer there, who I’d judged a talent competition with, said: ‘They’re inventing this new show on Radio 1 which will be on in the evenings and covers the sort of music that the NME covers. The producer of that show is coming down from Newcastle – why don’t you give him a ring and take him out for a drink?’ So I phoned up Jeff Smith, who had just joined Radio 1, and we went out for a drink.

About six months later, Jeff very kindly started inviting me on the programme, which was presented by Mark Goodyear. I was on the show once a month to talk about new music. And then Mark went on holiday for four weeks, and instead of getting an in-house deputy to stand in for him, they tried out four different people across the four weeks; I was one and Jo Whiley was another one.

“We stood up in a state of shock.”

Later on, Mark covered Radio 1 breakfast and there was a seven week gap where they needed someone on the Evening Session, and they put me and Jo together. There was lot speculation about the changing line-up, and the rumour in The Sun newspaper was that Nicky Campbell was going to get [the permanent Evening Session DJ slot].

Matthew Bannister ran Radio 1 at the time, and me and Jo went into his office and sat down, and he said: ‘I just want to thank you very much for all your hard work.’ That very much sounded like the start of, ‘… and now would you please never darken our door again!’

But he actually said, ‘We’d very much like you to carry on. We’ll offer you a one-year contract… thank you very much and welcome aboard.’

We stood up in a state of shock, thanked him, walked to the lift, got in the lift, the lift doors closed, and we just started hugging each other going, ‘Waaaah!’ We started properly in October 1993.

Why do you think that show ended up being quite so influential?

Why do you think that show ended up being quite so influential?

Music was quite interesting. We started just before Britpop, when grunge was probably the primary force. There was something happening in Britain – Suede had had a record out by then.

We were playing bands like Therapy?, Suede, Nirvana – and then everything changed in one week in April 1994.

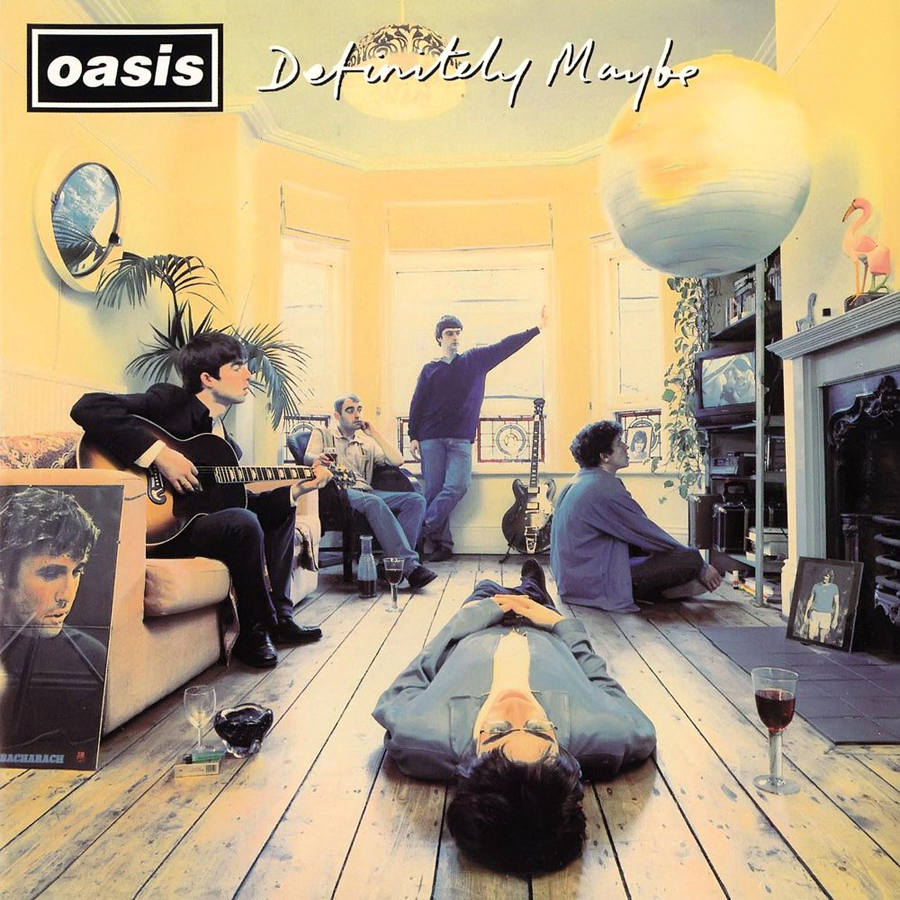

Radio 1 did a week of gigs in Glasgow – I think The Boo Radleys were headlining, and Oasis were first on the bill. Oasis did their first live set for Radio 1 [on the Evening Session] on the Tuesday or Wednesday night, and the following day Kurt Cobain kills himself. Without its figurehead, grunge begins to unravel, and with the arrival of Oasis, Britpop is born – all within about 48 hours.

“‘our’ people were now marauding through the Top 40.”

That started a whole new thing for the rest of the ‘90s, when alternative music suddenly finds itself very firmly in the mainstream and in the chart. Up until 1990 there was a lot of indie and alternative bands, but not many of them made it to Top Of The Pops or the Top 40. A lot of great records – early House Of Love, Inspiral Carpets – never made the chart.

But by 1994, all of these bands are knocking on the door of the Top 40. It became a big mainstream thing. And the place you could find who the next [big band] was going to be – and find interviews with ‘our’ people who were now marauding through the Top 40 – was on the Evening Session.

And then you started a record label – Deceptive Records – with the best distributor in the world! I have an Elastica gold record in my loo in Brussels. Where’s yours?

Mine’s in my office – but the one I gave my mum and dad is in their bathroom at home, in the house where I grew up.

The easiest way to lose a lot of money very quickly is to start a record label. We got a little bit lucky, though, with Deceptive. When I was at the NME I criticised a lot of major labels for how they dealt with bands, how they A&R’d them. At the back of my mind, I thought if the moment arises, I’ve got to prove we can do it in a different way.

We started Deceptive with £3,000 in the bank, putting out the first Collapsed Lung record. I knew the boys from Blur – they’re from Colchester and I’d written about them in the NME – and Damon recommended me to Justine Frischmann, his girlfriend who’d just started a band, ‘Maybe you should go and talk to Steve.’

[Elastica] had loads of record labels after them – MCA and various others were already in. I took Justine for a drink in a terrible pub, The Cambridge in Cambridge Circus, and said, this is what I want to do: a 7-inch only release. And I want it to sound like Teenage Kicks by The Undertones, but look like (White Man) In Hammersmith Palais by The Clash, with an incredible picture label.

I could see her thinking, Sounds like a risk, this! In the end, I told her the monkey story.

Tell it again.

Tell it again.

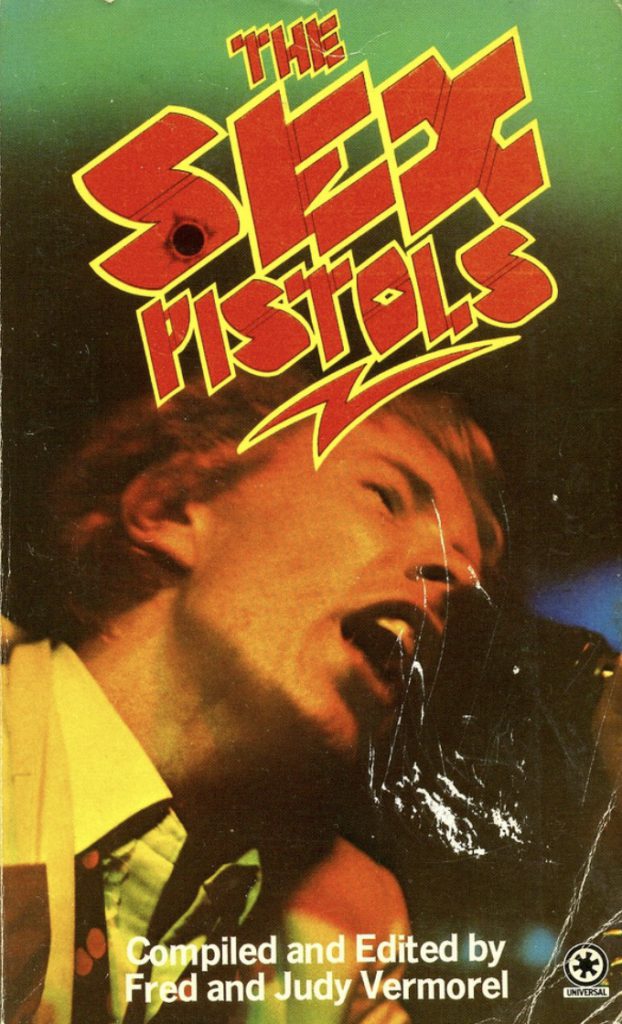

Fred and Judy Vermorel were writers in the punk era, and wrote one of the first ever books about The Sex Pistols. They reinvented themselves as social scientists and conducted experiments – one of which was to try and find out if [humans] have a natural, primal reaction to certain things; are we attracted to certain consumer goods?

So they hired a monkey, put it on a stool and gave it various items from around the house. They showed it a toaster and various other items.

They gave the monkey a CD. The monkey took the CD, looked at its reflection in the disc, and then threw it away. They gave the monkey a 12-inch piece of vinyl. The monkey held the 12-inch piece of vinyl, and do you know what it did? It got a hard-on.

And that’s why vinyl will never die. And it’s the story I told that meant I managed to sign Elastica.

We hear a lot that ‘guitar music is dead’ today. What do you think of that?

I think it’s nonsense. One of the things people think about is: Okay, we done an awful lot with guitars, and there’s not an awful amount more you can do which is different. But there’s an awful lot you can do with the lyrics and emotion of guitar [music]; you’re never going to run out of things to say.

Every songwriter has had a different upbringing and a different set of experiences, and if you put those down on paper, you’ve got loads of unique, different takes on life. Creatively there’s still something to be had out of the guitar scene. At the moment, there’s quite a split between what people are saying south of Watford, and what’s happening the further north you go.

There are thousands of guitar bands touring successfully in the north, and who can’t be bothered to come to London to play for some folded-arm critics who have moved on and think guitar music is not credible at the moment.

We need a new wave of something exciting.

We need someone with something to say who engages with people. The thing about Britpop is that it was very easy for the audience to want to be the people who were in the bands. That’s crucial sometimes to pop music movements.

“it was very easy for the audience to want to be the people who were in the bands”

Even Damon, in the first interview we did, quoted that thing: ‘All the girls want to be with you and all the boys want to be you.’

It was very evident with Elastica that within six months, all the girls at the gigs looked like either Donna or Justine; every charity shop in Britain must have had their racks cleared by teenagers wanting this slightly mod look.

What is the new exciting music today?

What is the new exciting music today?

I really like music which has an element dissent about it, but has a real humanity to it as well.

The bands I’ve really enjoyed over the past year? Watching IDLES, who I came across in Bristol, 2016 – their album Brutalism was my favourite album of [2017].

They’ve just signed to Partisan, I believe.

They’re one of the most exciting guitar bands out there. Them and a band called Shame are really good. And there’s a band from Hull called LIFE who are really good as well – they’re influenced by punk but they have a different way of expressing the ideals of punk.

If I was still at the NME, we’d have taken these three bands, created a name for a scene, done a two page spread on them and they’d all be in the indie charts the next week.

Why did you resign from the NME?

Why did you resign from the NME?

I was getting a little bit frustrated, and then Danny Kelly, the editor, announced he was leaving. Various people were going for the job; I was invited to apply for it and did the first interview but none of us got a second interview.

There was a black mark against quite a few of us because we’d been involved in some industrial action about 18 months beforehand. I don’t think the publisher wanted any of the people who formed a picket line outside his magazine to be running it!

They brought in a new guy from the Melody Maker, and I didn’t really rate his judgement of music, so I rather petulantly resigned on the morning his [appointment] was announced.

What about 2009 when you officially left Radio 1?

When the Evening Session finished in 2002, I stayed on at Radio 1 presenting a show or two – but I’d already started at 6Music in 2003, and it was the nearest [I’d experienced] of being part of that pirate radio spirit we had at Q102.

It was quite a small gang of people in an office, with no-one listening! That meant we could get away with an awful lot. It was anarchy at times.

Do you like subversion?

Yeah, of course. One of my journalist heroes, Mick Mercer – who used to edit ZigZag – once sent me a photo he’d taken of me in a promotional T-shirt for the ‘Firebomb Radio 1’ label. In the caption underneath it he’d written, ‘In case of punk revival, break glass.’

How do you expect the audience of 6Music to grow in the coming years?

How do you expect the audience of 6Music to grow in the coming years?

It’s difficult now because we’ve got over 2m people. There’s a lot of people who still don’t know about 6Music, ludicrously enough. If we were a different station, there might be a temptation to try and grow too quickly by trying to make the station a bit more commercial. But so far we’ve resisted the idea of playing to the lowest common denominator.

One thing 6Music is getting quite conscious of is how to always engage the next wave of audience; all radio stations, particularly Radio 1, have a problem with audiences growing up with them and staying with them, but newer audience not joining. Radio 1 is obviously trying to claw back people to radio from [alternative sources of music]; young people get music on YouTube or Spotify.

That’s going to happen to all stations sooner or later, even 6Music has got to be thinking: ‘How can we get involved in musical tastes of people who are between 16 and 30?’ We have to entertain and we have to be authoritative, and prove we bring something to their life as a music fan they can’t get anywhere else.

What do you think about the cultural impact of Spotify and Apple – personally and as an employee of the BbC?

It’s a hard one. If I was a musician, I’d struggle with the idea of Spotify. As a fan, I don’t really use it that much. Occasionally I’ll download something via iTunes, but I’ve never listened to Beats Radio or anything. When it flashes up on your phone, ‘We can do a playlist based on your musical choices!’ well… no you can’t. You just can’t.

Most people reading this will have a musical taste you can’t replicate with an algorithm. It’s never surprising enough.

Spotify will be really important, and people [in the industry] are starting to look at Spotify playlists in the same way they look at radio station playlists.

What about the idea that streaming will replace radio?

It depends what streaming is – is it the new radio, or is it the new way of building a collection of music?

It will be a huge challenge for radio, but if radio demonstrates it can still do things that mechanically-arrived-at playlists can’t do, I think there’ll be a future for radio.

People who really like music like hearing people talk about music, and you can’t do that with a streaming service.

Can you describe the typical Steve Lamacq day?

Get up, look after my young nipper, and then start work about 9am. I’ll do the running order for the show, which can take any length of time – it’s like making a compilation tape every day. Then I write some ideas, a couple of emails back and forth about features on the show, and then I do an hour’s worth of listening and try to do a bit of writing.

I get hundreds of emails and I can’t get back to them all – there’s 16,000 unopened on my BBC account at the moment – and I do as much as I can every day. Then I do the programme, meet someone for a drink, go to East London to see a gig, go home, start again. One day at the weekend, I have to do about five hours of listening just to catch up.

the legend is that Steve Lamacq goes through hundreds and hundreds of demos every day – is that true?

Not every day, but every week, yeah. You could take one of my [favourite] CDs from my office so long as I could swap you for something from a new band; I’d still swap what I know for something I don’t know.

But 99 out of 100 things can be terrible!

You can go for months without finding a band you fall in love with.

So you’re like a treasure hunter.

I don’t know how to describe it, really. I’m quite a nice bloke but I am quite selfish. This desire to find something partly has its roots in selfishness.

I want to feel that excited again by the last time I saw a band who were that good and made me feel alive and exhilarated. Doing all the things you did as a kid as a music fan – learning the words, reciting them in your head, creating images.

It sounds like a heroin addict trying to recapture their first high!

It sounds like a heroin addict trying to recapture their first high!

I personally wouldn’t use that comparison. And I don’t mug old ladies – not that I’m saying heroin addicts do.

There is a certain addiction to it. At the stage I typically see bands, they’re at their most raw and exciting. I’m not saying [every band] will flatten their sound out, lose the plot or become hugely famous, or that you’ll end up seeing them in massive venues where it just won’t be the same.

I saw Coldplay in front of 30 people at the Camden Falcon and there was something really special about it because they were completely unaffected by the music industry. It’s then, when there’s a real innocence and natural demeanour to the bands, that they’re at their most honest in a way.

In an interview with Radiohead once, with Thom and Ed, I asked them what the best era of Radiohead was, and they said: ‘When we used to rehearse in the village hall before we put anything else out, because at that point no-one had any expectations and we could be whoever we wanted to be.’

The next bit, when you start playing gigs and you’re getting better, you’re at your most natural and thrilling; I want to see that bit, I don’t want to see the clapped out bit when you’re playing the O2.

Why do you think demos are often so much better than the final recorded album?

Maybe not so much these days, but certainly when you used to find bands signing to a major label, it was, ‘Go back in and do that song,’ and it didn’t sound anything like it sounded [previously] – far too polished.

[Major label A&Rs] used to take the soul and energy out of records. Producers just used to rinse them of all emotion. The was one reason why I didn’t really like major labels.

Was John Peel your inspiration?

The great thing about Peel was that you didn’t have to like everything that he liked – obviously, he liked a load of stuff. Some of it, I thought was utterly unlistenable – but you admired the fact he found something in it. It became quite fascinating trying to find that thing he liked in it; it was almost a challenge. Some things were absolutely immediate and you got them right away and other things were like, I don’t understand this at all.

The great thing about John, the thing we miss most not having him around, is having someone who stands for all the things he stood for. When John died, in the [music] media, we lost our moral compass. Someone who utterly believed in the BBC as a public service broadcaster as an avenue for anyone – doesn’t matter where you’re from or how much money you have – to get on the radio.

Peel was the absolute beacon of accessibility. Regardless of stature or talent, if John liked it, he would play it.

It’s harder to get [your music] on national radio these days. Peel gave us a directive to open your ears, and if it sounds good, play it. People have lost that.

… yeah, we’ve lost John Peel but we have Steve Lamacq. Some say you’re the John Peel of today.

We’re much different people, in a way. Though there are bits about what I do which I’ve inherited from John, I think.

You fight for music. You fight for authenticity – for giving a space for new bands. I’ve seen you give a speech about small venues because you think it’s important for people to have the opportunity to express themselves. Are you conscious of how important you are – how you impact people’s lives?

I don’t think about it. I really hope that when I play a record, there’s someone out there who likes it.

I must admit, I went to see IDLES’ last London gig, at the Village Underground, I had four or five people who were heading towards the front, stop and say, ‘Thanks very much – I heard this band on your show.’ And, yeah, I’m chuffed that we can still get a band like that, put them in front of people, people will understand it and we can all celebrate the fact that, had it not been for 6Music, who knows.

Is that your purpose? Have you reflected on why you might be doing this? You say you’re selfish, but you actually like bringing pleasure to other people.

Someone’s got to do it; someone’s got to be there to give the people who don’t have a voice, a voice. I work pretty hard at it. I research a lot and I try to make sure we’re informed enough to know what the best stuff is.

I often see lists of, ‘Here’s bands to watch’ on websites or in magazines, and you think: ‘Half of these aren’t any good!’

I’ve always endeavoured to build trust with whoever reads [me] in the NME or listens on the radio. I’ve always enjoyed being a thorn in the side of the music industry in some ways, just because someone’s got to.

Are you idealistic?

I don’t really think about it that much. I’m coloured by a lot of the music I listened to in my teens. I’d like music to keep moving forward and surprising people and I’d quite like to be a part of that.

Music should have something to say, even if it only says it to a small bunch of people. I’m just the same as I was when I was 13, sitting next to Graham Diss in double history, showing off about a band I found out about on John Peel’s programme. ‘You still listen to them? I’m now listening to this…’

But if what I do is about anything, it’s about championing the underdog.

Does it make you happy or proud when that underdog makes it big?

Sometimes I get emotional about it; if it’s a band that I really, truly like, it’s brilliant. A band no-one was interested in, where it took five years for anyone to take any notice, was Catfish & The Bottlemen. They were just doing it off their own backs.

I went on three tours with them, following them around, just for three dates. I saw them play to 30 people in Leicester, and… each time, it got a bit bigger.

I don’t really know any pop stars – I don’t have any [famous] musicians’ phone numbers in my phone – except for Van McCann from Catfish & The Bottlemen. He texted to say, ‘Come and see us, we’re doing Wembley.’ And I went, really though, it’s Wembley – I don’t like those places, it won’t be the same. But he said, no come along, it will be nice after all the [support] you gave us at the start.

So me and my mate Tom went to Wembley and… it’s huge! They come on and launch into the first song, and it looked like everyone, even in the seats, was on their feet going absolutely mad. At that point, you think, Good work everyone. I was really chuffed for them.

The five years on the road before it happened for them, living off pub grub, they really grafted – and now the work’s been rewarded.

Even now seeing IDLES get to the size of selling out gigs months in advance, it’s just really nice. When they were given a chance, they took it. And they’re good enough that they will now change people’s lives in the same way that they’ve changed mine.