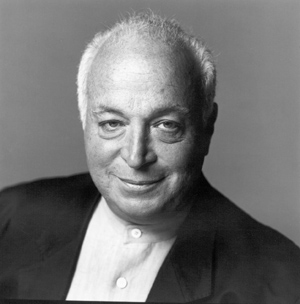

We wonder if there’s ever a day where Eddie Piller doesn’t look sharp as a razor blade.

We wonder if there’s ever a day where Eddie Piller doesn’t look sharp as a razor blade.

The Acid Jazz founder is never not nattily dressed, with an immediately recognisable look fashioned on the mod staples of his teenage heroes.

No great surprise, then, that his record label has always been one of the UK’s more tasteful indies.

Acid Jazz was founded in 1987 by Piller and Gilles Peterson, following Piller’s experience of running the Countdown Records label through Stiff.

Acid Jazz became a lightning rod for the burgeoning genre of the same name, as the label brought through the likes of the James Taylor Quartet, Mother Earth and Galliano.

For a brief few years in the nineties, things went mainstream – first with the Brand New Heavies, and then with Jamiroquai – before Acid Jazz settled back to being more of a specialist, though no less proud, concern.

Piller continues to run the label today, in addition to his career as a DJ, podcaster and all-round King Of The Mods.

[PIAS]’s Kenny Gates sat down with Piller in London to learn about his life, his choice to identify so strongly as a mod – and the highs and lows of Acid Jazz…

Before you entered the music business, what was your background?

Before you entered the music business, what was your background?

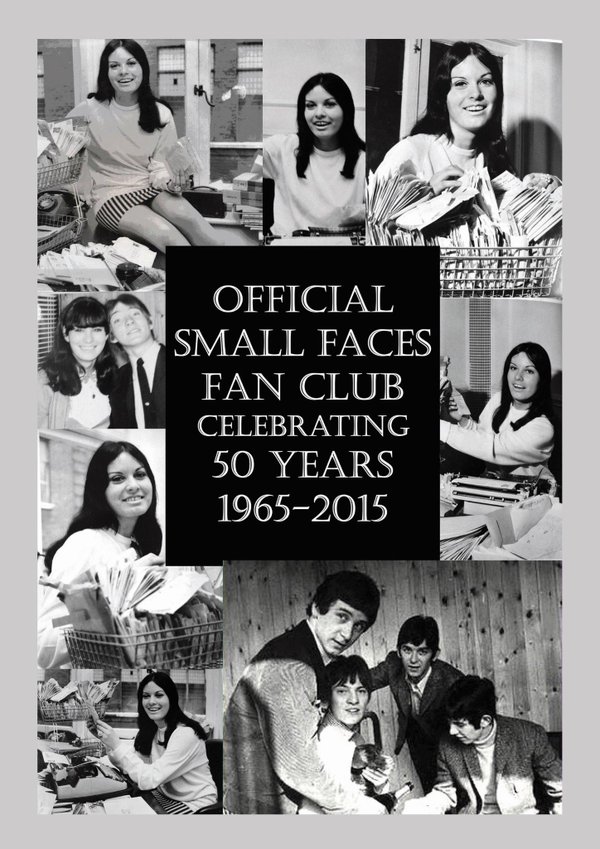

I’m from Essex, the son of an East End bookmaker and my mother, who used to run the Small Faces fan club in the 1960s.

I got interested in music through punk, like many people my age – particularly an Australian band called The Saints who were my favourite band of all time. They were on New Rose in France, and Harvest in England through EMI.

I got given a copy of [The Saints’] I’m Stranded when I was 14 by my mum’s friend who worked at EMI – she gave me a big box of records when I was at home, sick with chicken pox.

I went through them; Queen, Elton John, Rolling Stones, and then came across this single and I’m totally blown away, ‘Fuck! This is for me.’ So I started to go to gigs. Buzzcocks were a very important influence, Stiff Little Fingers, The Damned and then of course The Jam. And from there I became a mod.

Would you say being a mod defines you?

Yeah pretty much. Nothing to do with my mum and the Small Faces fan club, just purely because of The Jam and the mod revival in 1979. It’s convenient and fun.

Do you remember the first time you heard The Jam?

Do you remember the first time you heard The Jam?

No, but I remember the first time I saw them. I saw them maybe 55 times. But I think The Saints record I mentioned before had a bigger impact on changing my life completely. The Jam just became a natural place. I had a Saturday job and a holiday job; I used to save all my money to spend on records from Small Wonder Records in Walthamstow which was the most important record shop in London. And it had a label that released Bauhaus, Crass, The Angelic Upstarts (who I became a roadie for) and others.

What Alan McGee said about Rough Trade [in the Independent Echo] I completely agree with. I wasn’t part of that world. I can remember as a 14-year-old going into Rough Trade to look at some records and being laughed at.

The people who worked there were rather pretentious. It made me feel uncomfortable. So when I discovered Small Wonder, this shop was completely different, it was for people like me, it was the most important record shop of my life.

I’d go there three times a week. The guy behind the counter would say, Here’s this week’s four releases I think you’ll like. Singles were 50p, 28p, 70p – not expensive – so I’d buy 10 singles a week.

You had a relationship with the guys in Small Wonder. I never felt that with Rough Trade; I felt like they were sneering at people like me. I didn’t see the Sex Pistols, I didn’t go to the Roxy, so I wasn’t cool.

What was your education?

I went to private school, and I left school at 16 as soon as I could to work in the music industry. I wanted desperately to work for a record company.

I paid an Italian-English mod guy called Mario who worked in the Wardour Street Labour Exchange £5, which was a lot of money in 1979/80, to give me a call if any jobs came up for record companies.

All the record companies and music agents at the time only advertised their jobs in Wardour Street. After six weeks I thought ‘he’s never going to call’, then one day I got a message from him when I got home.

I went up to see him, bought him a pint in The Ship next to the Marquee Club and he said, There’s a job – here’s a number and I’ve not yet put the card up.

I phoned and the guy said come in for an interview. So I go in, and they gave me the job there and then. I become a motorcycle messenger office junior for a company called Avatar Records, which was in Pall Mall.

I worked with Pete Chalcraft who until recently ran Notting Hill Music in America. I was his junior and that was the beginning of my fantastic education. I stayed there for two years. I started as an office junior, became head of press, head of promotions, then the company went bankrupt so I found myself doing nothing, so had to start working for myself.

“Putting on gigs was easy because I was doing something for kids. Essex and east London was full of young mods and they didn’t want to go and see old guys telling them things.”

So I started DJing in 1981/2 at my local working men’s club in Ilford playing old records, soul music for mods.

Up to this time, all mod DJs were over 45. We were 17/18. I sold a lot of my punk records and bought a load of ‘60s soul and mod records, and we were out every week looking in second-hand shops for ‘60s records.

When I had enough I knocked on the door of the working men’s club and the guy said you can play records on Mondays. We used to charge 50p to get in on a Monday – within three weeks we had maybe 100 people.

Then I went to a bigger club up the road, not just an old club for working men, a proper nightclub. There we pulled 500 people every Monday. So the guy said you can have Mondays and Fridays. By now I’m earning very good money playing records. Once the club featured on a BBC arts show on the television, I knew I had made the right decision.

I remember saying to my dad, ‘I want to put on a big gig at Ilford Palais’ which was an old fashioned Mecca dance hall for 2,000 people. To sign the hire form you had to be 18 but I was 17 so my dad signed the forms, we put on a gig and it sold out. I thought, Fuck this is easy.

And it was easy because I was doing something for kids. Essex and east London was full of young mods and they didn’t want to go and see old guys telling them things. So we just invented it ourselves. It became very successful.

From there – bear in mind I’d been working at a record label for two years – so I thought, Well why don’t I start a record label?

What was it called?

What was it called?

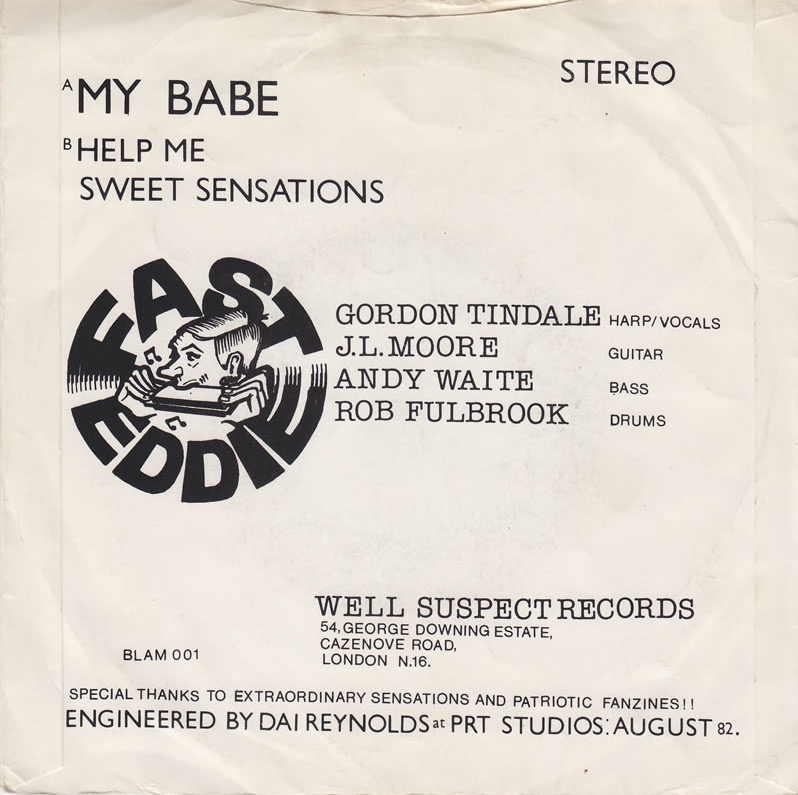

In June 1982 I started Well Suspect Records. I put out three releases. With the first one, I didn’t have a clue how to make a record, so I [replied] to an advert in the back of Sounds Magazine which said, Send us a cheque for £112 and we’ll send you 1,000 singles with a picture cover. So I made a picture cover with Letraset and I sent my cheque away but then realised I didn’t know about recording.

One of the guys at Avatar used to manage someone really big and he said, My friend runs a studio in Edgware Road, here’s his number, give him a call. The guy said, ‘How long do you want in the studio – it’s £13 an hour.’ I was only on £40 a week so that was quite a lot of money.

So I said, ‘I’ll have four hours.’ And the guy laughed, ‘What are you talking about mate? You can’t even set up in that time!’

I said I’d be fine.

I took an R&B band who were really tight and ran the session like a military operation. We had three run-throughs and then finished the recording. The engineer exclaimed, ‘Mate, no-one has done anything like that at PYE studios since the ‘60s.”

A month later I got the boxes back from the factory and that was my first record on Well Suspect – a band called Fast Eddie with a cover of a Sonny Boy Williamson song.

And then you do the second, third record on Well Suspect, you were earning your living as a DJ then doing records as a hobby?

Yes, but I forgot to mention that I was also doing a fanzine! It started late 1979, with me selling 20-30 copies of Issue No.1 at a gig at The Bridgehouse, which was an old punk mod venue in Canning Town.

I sold 100 of the second one, 300 of the third, 1000 of the fourth, 3,000 of the fifth – and by episode 15 I was selling 15,000 copies every two months, all around Europe, and all stapled by me. In the end I had to stop doing it because it was taking up an insane amount of time.

My friend was printing it at his work – he worked at a printers’ – so would wait for everyone to go home then he’d print my fanzine. Getting all the pages, putting them together and stapling them took at least a month with my friend helping me!

That became more profitable than DJing. At the same time I was selling second-hand records. My dad’s bookmaker’s shop was next to the pub where the Small Faces used to rehearse and play, The Ruskin Arms in East Ham.

“I wander in wearing my parka, just 17 years old, in front of these 30-40 year old Teddy Boys with love and hate tattoos on their knuckles.”

One door up the other way was an old record shop called Moondogs which specialised in Teddy Boy music. One day my dad mentioned that they had some records for me in their basement.

I wander in wearing my parka, just 17 years old, in front of these 30-40 year old Teddy Boys with love and hate tattoos on their knuckles. After they had finished laughing at me told me to have a look downstairs. It was the size of this entire floor piled from here to there with 1960s soul records. I used to spend all my time in that basement buying a thousand records and then selling them to my friends and people who came to the gigs. In ‘83 I opened a record stall in Kensington Market.

These were the 5/6 jobs I was doing – all self employed. By 1982 I was just working by myself, and I probably left Avatar in early ‘82.

One of my first jobs at Avatar was to drive Edwin Starr on the Northern Soul Tour of England. It was a real education. We were just discovering this music and yet here was a scene that had existed for 15 years doing the same thing. A real eye opener. An education.

So what happened between this point and launching Acid Jazz in 1987?

So what happened between this point and launching Acid Jazz in 1987?

I already had four record labels by the time of Acid Jazz.

Dave Robinson at Stiff phoned me up one day and said we’ve heard good things about what you’re doing from a friend of ours, Seymour Stein.

It turned out that Seymour Stein’s PA, Maxine Conroy, was a friend of Terry Rawlings who used to help me do the fanzine. Stiff were looking for a young A&R team to make some money out of the mod scene because they realised there was a second mod revival in ’83 but at this point it was still completely underground. It really was enormous. After the Jam split up and the original mod revival bands had faded away there was a whole generation of kids around the country with no bands to spend their money on.

Dave Robinson called me in and asked me, how would you like to run your own label, be an A&R consultant for Stiff? We’ll pay for everything, you’ll have your own office outside of Stiff, a secretary, a big salary, fucking yeah.

The first band I signed were called The Untouchables from LA. We had two chart hits – and they were the last big hits of the mod revival.

I had two good years of Stiff then in about 85/86 Stiff went bankrupt, so I had to do something else.

By now I was into jazz, I was friends with the jazz dj Gilles Peterson, and after a while we decided to start a label together – the mod scene had collapsed but this new jazz scene was thriving and throwing up a whole host of unsigned bands. That was Acid Jazz.

What came first, Acid Jazz the label or genre?

What came first, Acid Jazz the label or genre?

It’s not a big debate; it’s very simple. There was a jazz dance scene in London with DJs like Paul Murphy, Gilles Peterson, Baz Fe Jazz, Chris Bangs.

But Paul Murphy sold his records and that particular scene died with him. It was replaced by a much more eclectic jazz scene that added elements of Rare groove, Electro, Hip Hop, Fusion and organ jazz – championed by Peterson and Bangs and based around the WAG Club and Nicky Holloway’s Special Branch.

It didn’t have a specific name and was still known as the Jazz scene. I was a consultant at Urban Records at the time and thought there was some potential in capturing the bands that were at the birth of this new take on Jazz. John Williams (the A & R boss at the parent label Polydor) agreed and gave me and Gilles the chance to make an album. (The album was called Acid Jazz and other illicit grooves)

At the same time, and completely independently, we made our first Galliano record.

The name Acid Jazz was invented by the DJ, Chris Bangs and it was a bit of a joke because we couldn’t think of a name for either the scene or the compilation album – It came around because we were all into the early Acid House scene and were impressed with the energy and the sheer excitement of it.

Although the name Acid Jazz was initially a joke, the album did very well and the Galliano single came out a couple of months – we sold about 10k very quickly(mostly out of the back of a van). I was impressed.

So you became a label and Galliano took off. Was the tipping point for the label Brand New Heavies?

Yeah. After 18 months Gilles Peterson was approached by Mercury/Phonogram to set up a version of Acid Jazz through a major – but I’d already worked with majors and I didn’t want to do it.

I was making records with no pressure from a boss saying, ‘You can’t do that.’ Gilles wanted the security of having a salary and working with people who knew exactly what they were doing.

He didn’t want to have to make a record and then sell it, promote it – he just wanted to make the record. It’s a very different attitude I think.

I didn’t want to work with a major – majors were shit. I saw this at Polydor and the way they treated music. They didn’t care about the music they just wanted to make as much money as they could; they could have been selling washing machines. I never really understood this but then I was quite young and naive – I thought you could make great music and then sell it!

So [Gilles and I] amicably split the label in two. He went to Mercury and I stayed indie. Then the Brand New Heavies kicked off in America, not in the UK. I licensed it through Delicious Vinyl in the States and that was it.

The UK reaction was lukewarm (the band had been dropped by Chrysalis just a year earlier after only one single) but as soon as DV got involved the situation changed overnight. We had acts like Tribe Called Quest, Young MC and De La Soul talking about the Heavies in interviews and naming them as the best band in the world; suddenly Acid Jazz was really cool in London because of America.

[video_youtube id=”FB8nIGKbpJY”]

Gilles left and set up Talking Loud with Phonogram. Did you and Gilles become rivals after that – did you fall out?

Gilles left and set up Talking Loud with Phonogram. Did you and Gilles become rivals after that – did you fall out?

We never fell out but we certainly became rivals. We used to take the piss out of Talking Loud because they would spend loads of money on international campaigns all around the world and we would just do a little bit of advertising in the same magazines but we’d get the editorial because we already had an international fanbase.

I never fell out with Gilles but we were more successful and I’ll tell you why: because majors are stupid, okay. They never know what they have got until it is too late.

Talking Loud had the Young Disciples who were a British soul band a bit like the Brand New Heavies but maybe even cooler – the one album they made is superb.

“This is why I didn’t want to work with a major. It’s all about politics; who is your friend in the boardroom, all that old shit.”

[The BNH] were in the American R&B charts for a year and sold a million copies of their debut but Talking Loud didn’t even release [the Young Disciples’] album in the States. It came out four years later, far too late to ride the zeitgeist.

This is why I didn’t want to work with a major. It’s all about politics; who is your friend in the boardroom, all that old shit.

I was never interested in that. Sometimes our records sold, sometimes they didn’t – but at least we got to put them out. Half the time Talking Loud didn’t get their records put out and that was a real shame because they made some brilliant records.

Did you ever have a moment where you were overwhelmed by the business you’d created? It started off as a hobby and then become a commercial enterprise.

I had several businesses including four subsidiary labels, a magazine, nightclub [the Blue Note in Hoxton], a big successful merch company, a bar, both book and music publishing and two warehouses; at the biggest point I probably had 50 staff.

I also had a recording studio in Denmark Street – and this was all tied together and all very successful for quite some time.

Then one day I got really ill and the doctor said it was caused by stress. I was in bed for three weeks and then when I eventually got out of bed I said: I don’t want to do this anymore. Eighteen-hour days were a thing of the past. So I gradually started closing things down.

I had a big argument with Mike Chadwick at Revolver, and for a variety of reasons we fell out very badly. I also had a big argument with Steve Mason at Pinnacle, plus I got sued for the samples which cost me a lot of money.

I realised this wasn’t why I wanted to be in the music industry. Then the council said: ‘We don’t want your nightclub here anymore.’ That was the real blow as I was really enjoying the Blue Note – it had the excitement of the early label.

“I got very bored, very pissed off, and I started to get rid of all the areas of the business – literally.”

I got very bored, very pissed off, and I started to get rid of all the areas of the business – literally. Getting it back to a manageable cash flow was always really difficult.

The reason I bought the nightclub is because as a label, we never had enough money: we were turning over £5m or £6m a year and the company had a £30k overdraft from the bank. I bought a derelict nightclub, rebuilt it and then re-mortgaged that to get money to cash-flow the label.

All indie record labels go through the same lack of cash flow. It’s like an inverted pyramid: you sell one record to make two, then sell two records to make four and it has to keep sustaining itself. Eventually, the corners are going to fall off the pyramid because you can’t exponentially grow your business turnover every year.

We grew it exponentially for 10 years and then we just couldn’t sustain it. I didn’t want to do it anymore, it was driving me mad. I just wanted to sit in the studio and make records.

So you had to choose between being close to the music or the business?

Yeah and I chose records. I got Dave Robinson to work for me for two years to get rid of everything: I wanted to finish it with a team of four and a much smaller office.

Some people had been with me from the beginning and I had to let people go. They didn’t like it, I didn’t like it. I didn’t want to do it, so I got Dave Robinson to do it and he took most of the shit for it.

Acid Jazz went out of business?

No, but could have done. We had some difficult times financially but there wasn’t a time when we didn’t pay anybody.

The vagaries of cashflow meant that sometimes we couldn’t pay people for three or four months. Sometimes people get angry about that, other times people go: ‘Well, as long as I get paid.’ It became more shit to deal with so I didn’t want to do it.

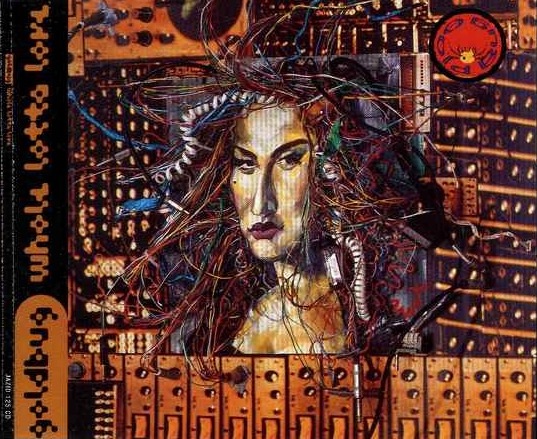

You mention lawsuits about samples. Tell me the story of your Goldbug single, Whole Lotta Love.

You mention lawsuits about samples. Tell me the story of your Goldbug single, Whole Lotta Love.

That is the thing that really fucked me off. This was a test case in English copyright law, which is a succession of precedents.

The finished master had a sample in it. We had paid to have the sample re-recorded but unfortunately, it wasn’t and eventually the judge decided that our contractual caveat/disclaimer about having samples re-recorded provided us no protection – as we were the final exploiters of the copyright which fundamentally contained elements that we did not own.

This allowed the publishers to get involved over an ‘unauthorised exploitation’ scenario. It was a disaster and tied me up for over a year.

That pretty much finished my time in the music industry. After that we went from being a very successful massive independent label with our own percentage of the annual [market share] in Music Week to being an also-ran indie.

It was all down to that court case. It hamstrung the business for over a year and cost serious amounts of money.

[video_youtube id=”lpgVxWvTlQs”]

And that’s why you got sick? because you were stressed by that?

Probably yeah. That was in 97, and it still makes me angry today!

Jamiroquai: what’s the story there?

Jamiroquai: what’s the story there?

The manager of the Brand New Heavies brought me this kid. I originally thought it was a black woman when I heard the demo!

I said, ‘Where is she?’ We were in Denmark Street and he said, ‘Look out the window.’

There’s this kid wearing a big hat, pony skin trousers, a poncho thing in multicoloured rainbow stuff and Adidas gazelles. I laughingly said: ‘I don’t believe that kid sung that demo.’

On the demo he had sung over a Brand New Heavies instrumental so we put that on the record player and he did the whole thing in front of us, live.

There were three staff plus a couple of people from the office next door, who had come round to see what the racket was, ‘What the fuck is that?’

“[Jay Kay’s] advance was £2.5k for the first album. He took the contract away, got it checked out, came back, signed the deal and we picked up his publishing as well.”

He’s singing and doing that little dance that he made so famous, and so I immediately offered him and the manager a contract. They both agreed.

His advance was £2.5k for the first album. He took the contract away, got it checked out, came back, signed the deal and we picked up his publishing as well.

We recorded the first single in my studio but it was very expensive – and from a creative perspective Jay was difficult to work with. One minute he wanted to work with James Brown’s musicians, then someone else, then try another studio. It was becoming very expensive, costing something like £35k to make the first single.

Bear in mind the Brand New Heavies album two years earlier, which sold a million copies, only cost £7k.

Suddenly I’m in an area I couldn’t cope with. So I took it around to most of the British majors; Lucian Grainge, Roger Ames, Sony (twice) and a few others but they all turned it down: ‘He can’t sing, he can’t write songs, he can’t dance – and that acid jazz thing is over.’

How did you deal with that?

I was getting desperate because I knew I couldn’t afford to make the album. We had two singles in the can, working on the third one. So I went to America where, because the success of the Brand New Heavies, Acid Jazz was taken much more seriously.

We walked into Columbia and they bit my proverbial hand off. So we did the deal – and this is where it gets interesting.

Sony at that time had a particular corporate structure which meant they wouldn’t allow us to deal directly with Columbia [US] – we had to come to Sony in the UK, particularly S2.

I didn’t want to do that because Columbia [US] were offering me a whole label deal: ‘We’ll take Acid Jazz, you can sign Paul Weller, Terry Callier, JTQ, we’ll bring the Brand New Heavies on board when they get out of a London deal.’ They offered me the world as a territory.

I went back into Sony [UK] and they actually said, no mate, we’re just going to have your artist off you. They were particularly angry that I had gone direct in the States as it appeared they had been questioned by head office as to why they had turned the band down in the first place.

I pointed out that we had a contract and they had already passed on the band twice – and laughed about Jay.

They then started approaching Jay directly and offering all kinds of inducements to break the deal with us. In the end I felt we couldn’t stand in his way. His next advance from us was 5k – they offered a hundred times that to break his contract – as well as all his legal fees.

Fair dos to Jay, a lot of artists would just have walked away from us – he made sure we got properly paid. We still had publishing and I did a deal with EMI Music where they picked up the rest of it and paid us an over-ride. In the end it was a very beneficial deal for Acid Jazz.

[video_youtube id=”OPkjnRIdQXQ”]

Still, it must have been bad to have Sony UK reject the artist and then steal him from you.

That was one of the problems I had with majors. All Sony did was to reinforce them.

It was very frustrating at the time but I had to laugh when I heard their head of A&R claim on a Radio One interview that he had discovered this genius kid but that he wasn’t ready so he had given him to a little East End label to develop.

He has just won a lifetime achievement award for his A&R genius but had nothing to do with signing nor developing Jamiroquai to Sony, that credit was with a woman called Faith Newman at Columbia in the States!! No shame these people…

Would you say you paved the way for the likes of Mo Wax, Wall of Sound and other labels?

Would you say you paved the way for the likes of Mo Wax, Wall of Sound and other labels?

Yeah pretty much. Not just us but there was a whole movement of like minded indies. Me and Gilles doing Acid Jazz and Talking Loud were the first two.

Labels like Dorado, Mo-Wax and Wall of Sound came along soon after… quickly followed by all the labels spawned by Trip Hop and Drum and Bass like Metalheadz and Good Looking. It was an exciting time for the indie scene.

I think these labels re-defined the independent sector for dance music – I don’t mean the house-based indies (of which they were many).

Up to that point the indie scene was all about guitars. In fact the word ‘indie’ became synonymous with guitar bands after us too.

As a mod, did you dream of signing Paul Weller?

As a mod, did you dream of signing Paul Weller?

Yeah, I nearly signed him. We negotiated for quite a long time. I’ve released a few records by him over the years. I didn’t think he was finished after The Style Council – a few people in the industry said that they thought he was. Within 18 months he’d done Wild Wood, and album that should really have been on Acid Jazz.

At that time, I’d been negotiating with Polygram to buy the whole label. In the end they bought Mo Wax instead. It was via-A&M but I was most interested in working with London who I respected immensely.

“the outrageous negotiations that we had with Polygram about buying Acid Jazz… fucking extraordinary.”

If you actually knew the outrageous negotiations that we had with Polygram about buying Acid Jazz! It’s far too much to go into here but it will be in my book eventually. It was fucking extraordinary. The inducements were off the scale. Many of millions of pounds – I really enjoyed negotiating with Lyor Cohen and Roger Ames. I suppose because in my heart I didn’t really want to sell up, I was pretty over the top in what I was asking for.

In the end I just pulled out. They wouldn’t let me include Paul in the deal and that was a red line for me.

Do you regret it?

No. I’ve had a great life and been all over the world and had some of the most incredible moments.

Being a DJ has been a laugh too; I’ve DJ’d at some pretty wild parties for people like Ray Charles, Pele, McCartney or Sylvester Stallone in tiny little places.

I’ve had a fantastic time. I’m not rich, I’m not poor but I wouldn’t change a thing.

Recently you did a deal with [PIAS] for the ‘new’ Acid Jazz. What was the process of wanting to revive the label?

I got cancer six years ago. I was told I was probably going to die, so I withdrew completely from the music industry.

I didn’t want to stop the label so I brought in a succession of label managers and pretty much gave them a free hand musically. I’m not sure it worked though because Acid Jazz has always been a soul based label and some of the things we did were a long way away from the original ethic.

In the end, Dean Rudland – who has been with the company (with a break in the middle) since 1990 (and is now my partner) stepped in and looked after things until I made a full recovery a few years later.

“I got cancer six years ago. I was told I was probably going to die, so I withdrew completely from the music industry.”

I gradually got excited about music again and the thought of signing bands with a partner who took after all the boring stuff got me back into the idea of making music. The [PIAS] deal seemed the perfect solution. We own a very big catalogue and are approaching the 30th anniversary, it was time for a change. Also, some friends like Jeff Barrett at Heavenly and Sarah Bolshi from Sunday Best told me that it was a great place to be!

The thing about [PIAS] was that we worked with you and Edwin 20-25 years ago, and I know that you both had a certain fondness for the music that we made.

I think we can still make great records; I don’t think anyone is making the kind of soul music that we are into. That’s not to say it’s ever going to be fashionable again but it is valid – and [PIAS] has given me the opportunity to sign some of my favourite artists.

I’m really excited, we’re having a really good time just being a label; I forgot that if you can divorce the business of music from the making of music you can have fun. So now I’m just going back to what I used to do before I became fucking boring. Thanks to [PIAS].

You once said to me: ‘I’m a genius, Kenny!”

Yes, Kenny. We had been drinking all day at that point in time!

Of course drunkenness and truth…

… are good bedfellows. Many a true line is said when you’re drunk – and of course, I am an egotistical lunatic.

Have you got a proudest moment?

Have you got a proudest moment?

Being told by Paul Weller’s mother to lead the 6,000 crowd on his 50th birthday in a chorus of, ‘Happy birthday dear Paul’, was very embarrassing but quite fulfilling. My actual proudest moment is when I persuaded the singer, performer and legend Terry Callier to come out of retirement.

It took me three or four weeks to track him down and then I phoned his house in Chicago every single day for a month. First off they said: nobody lives here by that name. In the end he finally took my call and said: ‘Look what do you want? I’ve given up. I fell out of love with music a long time ago, stop phoning.’

I said: ‘I’ll bring you and your daughter on holiday to London; I will put a band together, I’ll hire a little club, the 100 club – and you get up on stage and sing a few numbers. If you like what you see, let me release a record’.

In the end, he was blown away so we released a single and he earned more money from that one single and the deal that followed than he’d earned on all his albums in the ‘60s and ‘70s

And was Whole Lotta Love your worst moment?

Indeed it was. Every aspect of that deal and what went wrong taught me a lot about the risks of having a hit record!

Do you think it’s a challenge to create the self-confidence needed to be able to survive as an independent in the music business?

I love what I do; I also think I’ve got superb musical taste. Not a lot of people agree with me but that’s what I think. How many people have done what I’ve done or what Alan McGee’s done or Daniel Miller, Dave Robinson? From scratch, without investors…

You’ve got to be pretty mad, you’ve got to believe in yourself because how many times do people tell you what you are doing is shit?’ Every day.

We had to be a little arrogant to stick to what we need to do. If we had listened to everybody telling how bad we were we would be digging a hole for ourselves. One we would never have got out of!