It’s been quite the week for the theme of independent music reunions.

It’s been quite the week for the theme of independent music reunions.

The Independent Echo’s lead interviewee this month, Chris Wright, has re-acquired the label he built, Chrysalis Records, alongside Jeremy Lascelles and others at Blue Raincoat Music.

Meanwhile, over in Ibiza, [PIAS]’s own Kenny Gates gave a keynote speech at the International Music Summit (IMS) describing his own experience of selling his (and partner Michel Lambot’s) business… and then buying it back.

Below is an edited version of that speech. Spoiler: It has a happy ending. Thank God.

The best part of what I do is working with incredible people at incredible labels – including our own.

These labels share with [PIAS] two common themes One: they push boundaries and innovate Two: they take risks.

And like any label that takes risks occasionally, mistakes can be made. But they are usually mistakes made in the pursuit of excellence.

I would like today to tell a story about how to learn from one’s mistakes.

Anyone who says they have never made a mistake is deluded. I am happy to hold my hands up and say that I have made plenty in my life and career.

I think I have also made some pretty good decisions… but I believe it’s our mistakes, and how we respond to them, that truly shape our character.

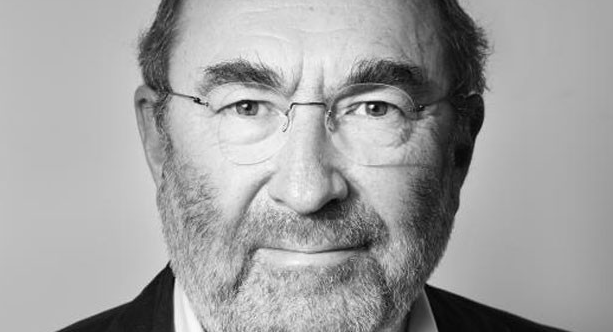

So, lets start at the beginning, Almost twenty years ago, my partner Michel Lambot (pictured) and I sold our company.

So, lets start at the beginning, Almost twenty years ago, my partner Michel Lambot (pictured) and I sold our company.

This in itself wasn’t a mistake. But how we handled ourselves after we sold it? Well, that needs looking at…

At the time, this looked like a great business decision – we were offered a lot of money and the creative freedom and resources to build on our existing success – what could possibly go wrong?

Let me set the scene. In 1996 our company [PIAS], which we had started in 1982, was doing pretty well.

We had a solid business working with all of the top independent labels of the day. We had just opened a new office in France.

However, we were frustrated at our lack of funds and our inability to compete with the majors.

We were finding it increasingly difficult to sign the artists and labels we wanted to work with and to keep hold of the talent we already had.

One of the main territories we had struggled to gain a meaningful foothold in was Germany.

We had a small office in Hamburg but for one reason or another we hadn’t really been able to make an impact there. Given that it was one of the world’s major music markets… this was an issue.

We had a small office in Hamburg but for one reason or another we hadn’t really been able to make an impact there. Given that it was one of the world’s major music markets… this was an issue.

Then, in 1996, we were approached by Michael Haentjes (pictured), the boss of Edel.

Before I go on I want to make this very clear: Although the ideas and dreams Michael had were ultimately doomed… he was a visionary and I have nothing but respect and admiration for him.

His plans didn’t work out but he had the guts to try.

Michael approached me with an idea. He wanted to expand Edel’s offering beyond the pop and jazz catalogues they were best known for. He knew Michel and myself wanted to create a bigger presence in Germany so he suggested we launch a joint venture – an independent sales force.

It made complete sense – he would provide the funding and resources and we would provide the expertise and content.

Things moved very quickly after our initial discussions and within eight weeks we had hired 10 people for our new company, ´Connected’.

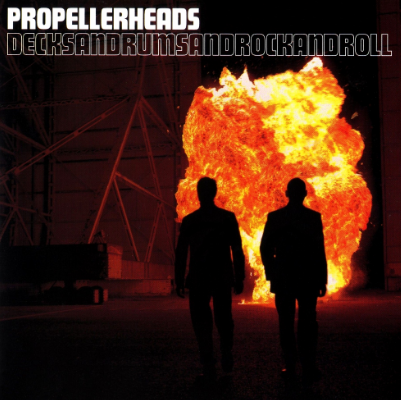

Our first release by The Propellerheads was a Top 10 hit. We were off to good start.

Connected quickly established itself as a viable business working with Mute, The Beggars Group as well a number of big local labels.

Two years later, in 1999, Michael Haentjes announced, out of the blue, that Edel was going public – to be listed on the German alternative investment market, the Neuer Markt.

Two years later, in 1999, Michael Haentjes announced, out of the blue, that Edel was going public – to be listed on the German alternative investment market, the Neuer Markt.

He had been approached by investors who wanted to buy into his company and who wanted to develop a successful music business using Michael and Edel as the hub through which to attract other acquisitions.

The key to this masterplan was scale. The investors wanted Michael to create scale fast and the best way to do this quickly was to go on a buying spree.

Edel had been valued at 27 x its profits, which by any standards was an impressive multiple, and Michael approached us offering the same multiple for [PIAS].

Michel and I were quick to reject Michael’s offer. It was good money, great money in fact, but we weren’t interested in selling – we felt we had a growing business with excellent prospects and, above all, attached a real premium on our independence. By this time, we had sold over 3 million Mr. Oizo ‘Flat Beat’ singles on F Communications and 500,000 Propellerheads albums – we were flying!

But Michael was persistent. He laid out a plan that would allow us to keep our independence alongside creative and operational freedom while receiving the resources to grow the company. He didn’t want to ‘own’ us, rather he wanted to provide the funding and support to maximise the potential of [PIAS].

So, after much deliberation, we agreed to sell Michael 74.9% of the shares in [PIAS] while retaining 25.1%.

That figure is significant because retaining over one quarter of the shares meant we received a lot of minority shareholder protection under Belgian company law.

In return Michel and I received a significant personal payment for our shares and on top off that were given a €25m ‘war chest’ to grow the company.

That’s Twenty. Five. Million. Euros.

We also both received a seat on the advisory board of the Edel parent company.

So a guarantee of autonomy, personal wealth, a big capital injection for the company and a seat on the board of the parent company. Where’s the catch, right?

I’ve got to admit – I thought it was the deal of a lifetime. And it probably was.

Michel and I promised each other we wouldn’t get carried away – we would stick to our principles and not allow ourselves to get overwhelmed by the money or expectation. It is worth mentioning at this point that while we were starting to get very excited about this proposition, not everybody working with us had bought into this idea.

Our Financial Director at the time, Phil Sassus, a thoughtful and professional guy, had taken a look at the offer and raised concerns.

His view was that the deal looked amazing but it didn’t reflect reality. How was this plan remotely workable? It didn’t make financial or economic sense. Not one bit.

Michel and I politely listened to his concerns, nodded along with his warnings – and then completely ignored them.

One of Edel’s core strategies was to grow through acquisition, to create scale and market share in order to drive revenues for their shareholders.

We were encouraged to take this money, this €25m war chest, and spend it. Fast.

Our instructions from Michael and the Edel board were: “Sign bands, buy labels, grab content and IP wherever you can. Grow the business.”

Edel wanted acquisitions and they wanted [PIAS] to start driving revenues through the group as soon as possible. They wanted us to start returning on investment.

Edel wanted acquisitions and they wanted [PIAS] to start driving revenues through the group as soon as possible. They wanted us to start returning on investment.

Not an unreasonable request in a normal business but as everyone in this room knows, we do not operate in a ‘normal’ industry. Suddenly we had a lot of new friends.

Overnight we were the guys looking for deals and with money to spend so managers, lawyers, label owners and anyone with anything to sell came calling.

You’ve seen this phenomenon in football in recent years. Money has poured into the big leagues around Europe and suddenly the cost of talent has a massive premium attached to it. Suddenly a player who was €15m one week is suddenly going to cost €25m because the buying club has had a big TV money windfall or a new Russian owner.

We were those guys.

But before we even got to the deals, we staffed up. To cope with what we anticipated would be a flood of new signings and acquisitions we started hiring, and hiring good people is expensive. And then we did some deals. Oh boy, did we make some crazy deals.

We paid advances to bands that even today make me squirm, and acquired labels for silly money. Some of which might be in this room.

A lot of people made good money from our mistakes. It wasn’t all bad; despite some of the bad business decisions, we do actually know what we’re doing when it comes to talent, and in amongst the terrible deals were some really good ones – we signed Sigur Ros, Mogwai, 2manyDjs and others during that period, so it wasn’t like we’d gone deaf.

During this spending spree we started to hear murmurs of disapproval from our friends and colleagues in the independent music community that we were over-inflating the market and driving the price of deals up. On reflection, this was true; we were overpaying and creating an unrealistic environment in which others were finding it hard to compete. In some ways we were acting just like the major labels we had worked so hard to distance ourselves from philosophically.

Then things started to go badly wrong.

First of all, we ran out of money. In 18 months we had managed to pretty much burn through our €25m. And to make things even worse Edel’s share price had crashed.

From a high of €126 the shares were sitting at just €2 and the grand vision of Michael Haentjes and Edel was falling apart.

As previously mentioned, Michel and I sat on the advisory board of Edel so we knew that the group was in trouble. [PIAS] was losing money but the group was … haemorrhaging cash.

At this point I want to say this: I believe Michel and I, along with the team we had, could have turned things around given more time. I genuinely believe that.

We had some really great labels and artists (albeit we may have overpaid for some of them) and some brilliantly talented staff. But the timeframe we were given to develop these acquisitions into a profitable business simply wasn’t long enough.

It takes time to develop artists, it takes time for labels to grow and nurture their rosters. Something the stock-exchange never understood.

We tried to do things too quickly, we didn’t allow time for our talent to breathe. Of course we failed, how could we not? And of course, eventually, we got the call from Michael.

He sat us down and was honest with us – things weren’t going well, there needed to be a major restructuring of the group. We asked him if he wanted us out expecting him to say yes but his answer surprised us. He didn’t. Instead he wanted to buy us out of our remaining 25.1% shareholding and fully integrate [PIAS] in Edel.

I say this with my hand on my heart – it took only one glance between Michel and myself before we said no. I didn’t want to be 38 years old, holding a big bag of cash but essentially jobless. And Michel felt the same. By this point we had been running [PIAS] for 16 years, we had built it from nothing, grown up with it, it was our life’s work and a huge part of who we were.

Selling that legacy on the back of what felt like failure? No chance.

That period had taken a big toll on both Michel and myself. We both suffered on a personal level, there were divorces, moments of depression, of great insecurity, too much drinking, over indulgence… it was a huge strain.

That period had taken a big toll on both Michel and myself. We both suffered on a personal level, there were divorces, moments of depression, of great insecurity, too much drinking, over indulgence… it was a huge strain.

In the last two years [PIAS] has launched an online blog, The Independent Echo, the raison d’etre of which is to celebrate the independent community as a whole.

As a contribution to this I have interviewed a number of music industry icons who have at some stage sold the companies they built; people like Daniel Miller (pictured), Korda Marshall and Chris Wright. They all have the same thing is common: they kind of… all regretted it.

They regretted it because the music industry, for most of us who work in it, is not just a job – it is a privilege.

This is an emotional business, a people business, a talent business – we are drawn to all of those things not just the money.

As an aside, let me remind you of a comment that’s always stuck with me, made by Roger Ames to Guy Hands after his acquisition of EMI.

Robbie Williams, one of the company’s superstar artists at the time, had called Guy Hands a ‘plantation owner’. When told this, Roger Ames shrugged his shoulders and said, “The problem is, Guy, the assets you have acquired have opinions.”

But coming back to our story – we knew [PIAS] had a future. We knew that what we had built was worth fighting for. We were utterly committed to making it work.

So, we made Michael a counter-offer: sell your shares back to us. And he did. For that I will always love him. He didn’t have to – but he did the right thing.

We found some new investors, put our own personal money on the table and got our company back. It was wonderful.

I could easily end the story there with a short summary of how we all lived happily ever after. But life is not that simple.

Having regained control of [PIAS] we had to face a lot of hard truths. For one thing, we were virtually bankrupt. The company was running on fumes and was a financial and structural mess.

We had to fire a lot of good people, which was terrible. And we had to face up to the fact that we didn’t have the managerial experience or expertise to run a company of that size. We were good bosses but lousy managers.

We put in place more efficient management structures, gave people new responsibilities and empowered them to play to their own strengths on behalf of the company.

We stopped micro-managing and reacting to everything on an emotional basis. If our German partners had taught us one thing, it was pragmatism.

We learned to take the emotion out of commercial decisions and to start thinking like proper businessmen… well, almost.

That doesn’t mean we stopped being creative, far from it, that has always been at the core of what we do and always will, but we learned to separate creativity from business and it was an important turning point for us.

And slowly but surely, by learning from our mistakes, we turned things around.

We embraced the digital world and technology right from the very start and built a modern music company. We made pragmatic acquisitions, signed some wonderful artists on sensible deals and slowly expanded our reach around the world: today we have offices in 16 countries.

We will always be grateful to the labels and artists who have supported us, to the staff who stayed loyal and to the independent community in general who have proved in recent years that they are the future.

So, let me leave you with this thought: Don’t have regrets, always think big.

But never be afraid to confront your mistakes, to admit you are wrong and to learn lessons from the past.

That is not a weakness – it is a strength.