It’s perhaps apt that the wintry wonder of Bon Iver’s For Emma, Forever Ago is indebted to a snowstorm of epic proportions.

Back in 1995, Secretly Group co-founder Darius Van Arman was working in a home providing overnight assistance to developmentally disabled adults in Charlottesville, Virginia.

It provided some pocket money for the young student, who was toying with the idea of dropping his mathematics degree at the local University Of Virginia.

He was increasingly realizing that his dream was making a living from music – a desire only heightened by other part-time jobs working in a record store and promoting local club nights.

Then, one winter evening, a blizzard hit. Van Arman was stuck at work for two days straight, with his colleagues unable to make it in.

As a result, he was given a bumper over-time paycheque of over $1,000.

That paycheque funded the release of a CD from his housemate’s band, The Curious Digit.

It also stretched to putting out a record from Richmond band Drunk; Van Arman also managed to score some them press in the UK’s Melody Maker.

“Six weeks later I got a cheque from Cargo in London for $350,” he recalls. “I was confused by it, but they wanted to buy 50 copies – our first distribution deal!

“My attitude at the time was: ‘This is easy! You send one CD out, you get a review, you ship 50 CDs, you do it again…”

It was a charmingly optimistic business plan, but it must have kind of worked – because these days, Van Arman is accustomed to shipping rather a lot more than 50 CDs.

He established Jagjaguwar – named using a computer program that randomly generated Dungeons & Dragons character names – in 1996, before teaming up with Chris Swanson from Secretly Canadian three years later in Bloomington, Indiana.

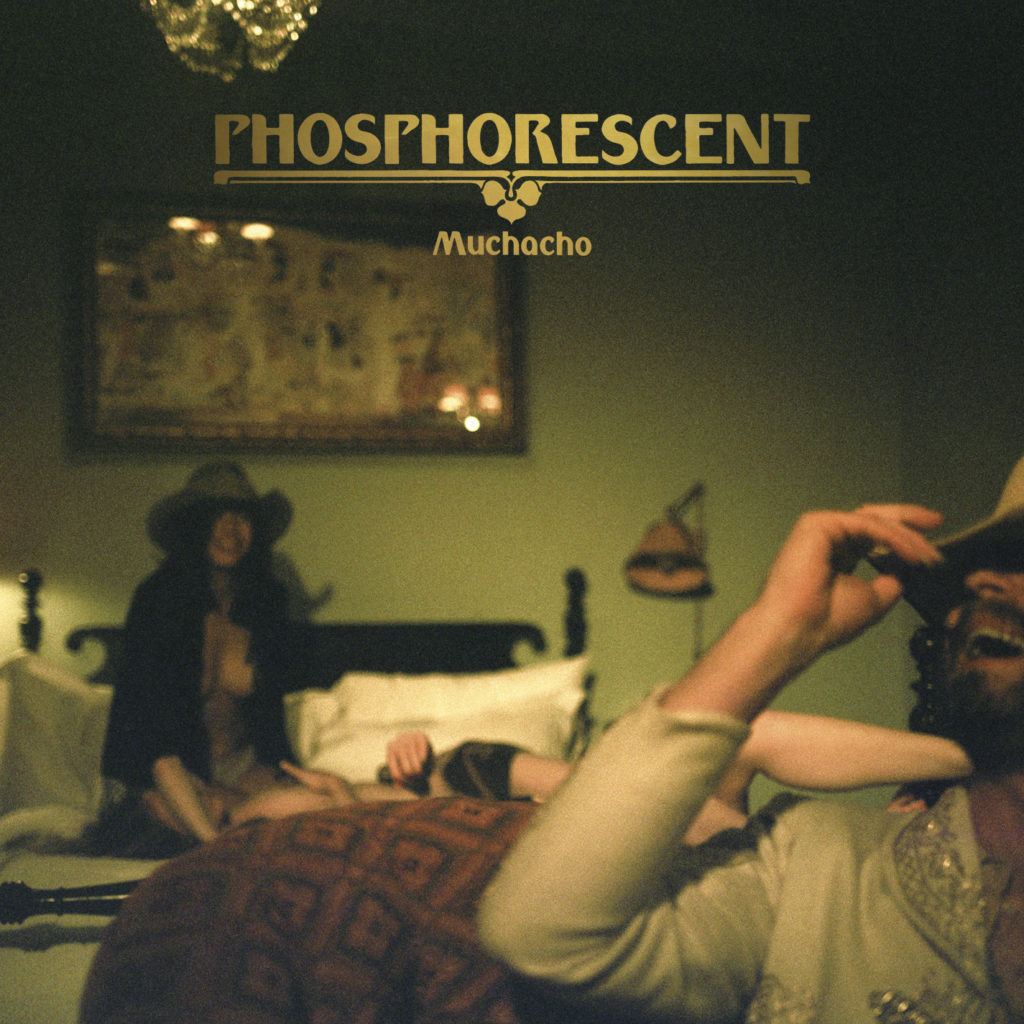

This team-up has fueled Secretly Group’s fantastic success ever since across labels such as Secretly Canadian, Dead Oceans and Jagjaguwar – with artists ranging from The War On Drugs to Kevin Morby, Phosphorescent, Angel Olsen, Anohni and Justin ‘Bon Iver’ Vernon.

[PIAS]’s Kenny Gates sat down with Darius to ask about the beginnings of Secretly Group, the perils of getting bigger – and the health of independent labels in 2016…

Why did you decide to join Chris Swanson in 1999?

Why did you decide to join Chris Swanson in 1999?

I had been working a lot of jobs to make ends meet while I was in the very slow process of dropping out of college.

Chris and I were talking a lot on the phone – in the pre-email era – about how to build up this business, and I expressed to him how I needed a business partner.

He eventually said yes, that he’d be willing to be my partner, but I had to move to Bloomington, Indiana to make it happen. So I packed up everything in 1999, left school and started this adventure.

How did you parents respond to this mad idea of going into the music business?

They hated it! But to their credit they came around.

My father grew up in Detroit, the son of a taxi cab driver and was lower-middle class. To him, education was the way out of that. He has a PHD in mathematics and was a math professor who worked for think tanks.

For him, seeing me drop out of college was evidence of me wasting an opportunity. He didn’t understand that this was a business we were starting and not just self-indulgence.

Then after I moved to Bloomington, Indiana and they saw the business build up over two or three years with all the hard work, my parents started to change how they felt about it.

How do you define the separation between Jagjaguwar and Secretly Canadian today?

We have different A&R teams on each label. At the very beginning when we were very small – there were five of us here in 1999 – we shared one room, which was maybe 150 square feet. We also shared one computer, one fax machine and one email address.

In the early days, anything signed to Jagjaguwar was something me and Chris Swanson felt passionate about; anything on Secretly Canadian was something Ben Swanson, Chris Swanson, Jonathan Cargill and Eric Weddle were passionate about.

We started Dead Oceans five or so years later, which involved a new partner, Phil Waldorf. Now we have three different A&R teams for each of the labels – they’re all distinct and pursuing a separate vision for each label.

So in a way, perhaps not knowingly, you mirrored the Beggars structure – with one umbrella company taking care of a handful of labels?

So in a way, perhaps not knowingly, you mirrored the Beggars structure – with one umbrella company taking care of a handful of labels?

It’s similar, but one big difference is that the Beggars companies all have different ownership.

Right now, the ownership of Jagjaguwar and Secretly Canadian is identical and very close to the ownership of Dead Oceans, which just has one additional partner.

It’s a collaborative setup. We never have a situation where more than one of our labels is trying to sign the same artist – it’s less competitive internally. I believe it’s different at Beggars.

Do you believe in indie consolidation – is that the way forward for independents?

Yes and no. The biggest challenge we have as independents is the scale advantage that the bigger companies have; can you ever compete with the majors if we’re continually having to rely on bigger companies for every function? How do we get out of that cycle?

There’s value in consolidating to a point where we can be more self-sufficient, control how you release things and dictate elements of commercial deals.

At the same time, though, there’s the fallacy that you can truly do it all yourself. If you go too far in the direction of consolidation and don’t rely on local partners to help you market expertly in each territory, that’s when inefficiencies and bloat emerge – you can’t move as fast as you need to in a quickly changing marketplace. We’re hoping we can find the sweet spot.

You seem to be the figurehead of the group – the frontman! You’re very active on the boards of AIM, Merlin, SoundExchange…

I’m definitely active with the trade associations. But when it comes to A&R and marketing, my partners have a more pronounced role than I do.

Many managers and A&R-orientated lawyers know who I am because I’m involved in some deal-making. But I’m not the sole primary figure.

Is it important to be friends with your partners?

Yes. Are you friends with your partners?

Yes!

Could you do it without being friends?

I don’t think so. It’s almost like being roommates. If you don’t get on, you might as well forget it!

Right! Also, being competitive in a declining market – although maybe things are turning around now – you don’t have a lot of time or energy for not making decisions quickly or internal tension.

The companies that have had tension internally have struggled to compete.

Isn’t it extraordinary to have built such an important business out of Indiana – the Brussels of America!

Early on we didn’t have crazy pressures that we were chasing – we were building slowly and organically.

I imagine other companies who started at the same time in New York City, for example, had much higher labour costs and higher rents to deal with.

Maybe that put pressure on them to shoot for things they weren’t quite ready for yet.

And there’s less groupthink in the Midwest than in the coastal big cities – where you go to see a hot band and all of the same [A&R] guys are in the room.

What was the moment that made the biggest difference to your P&L in the early years?

For Secretly Canadian, the first steady seller was Songs Ohia – Jason Molina’s music was really what opened up a lot of doors for us.

And then the big breakthrough internationally and commercially was I Am A Bird Now by Antony & The Johnsons, which won the Mercury Prize.

You licensed it to Rough Trade?

Yes, but originally we released it ourselves worldwide. For example, we sold over ten thousand copies in Spain before Rough Trade was involved. It’s our best-seller still in that market. We couldn’t press records fast enough to keep up with it. It was a big paradigm shift.

Then for Jagjaguwar, the first artists that had some international success and helped us get on the map were Black Mountain and Okkervil River. And then the biggest breakthrough for us was Bon Iver in 2008 – For Emma, Forever Ago.

How did you sign Bon Iver?

How did you sign Bon Iver?

Justin Vernon and his manager Kyle Frenette sent out a few copies of For Emma, Forever Ago to a few labels. Chris Swanson kept on coming back to it and said: ‘You have to check this out.’

Justin Vernon was in Montreal at the same time I was going there to spend time with some of our artists. Justin and I met up in a bar outside this place called the Ukrainian Federation. We drank a couple of pitchers of beer and chain smoked, we had a great conversation and the next week we decided we were going to work together.

We got an agreement done and then three or four months later we put out the record. It’s been a brilliant relationship so far. We feel very lucky to have had the opportunity to meet Justin and work with him.

Terry McBride recently said that being an independent label meant you were in the business of ‘monetizing emotions’. That’s a good way of putting things…

Yeah, I like that description. We don’t view ourselves as an entertainment company, we view ourselves as a music company. The distinction there is that entertainment companies are looking to monetize celebrity, fame and what’s culturally important even if it’s not musically brilliant.

We’re geared towards what’s musically brilliant and what’s culturally inspiring on an emotional and human level.

What would the Darius of 1996 looking at the business now be thinking?

I think he would be proud of what we’ve built. I don’t think I’d look at what we are now and feel like we had changed the essence of who we are.

We’re finding new ways to introduce great artists to the world in a way that’s true to our ideals. And, yes, there has been a transition – as you grow there’s only so many relationships you can maintain on a personal level; artists, employees and friends I wish I had more time for.

So maybe the idealistic part of me in 1996 looking at what’s happening now would question whether we’d become too big; whether there was a way we could be doing what we’re doing while still keeping it small.

But the practical part of me now would say that what has occurred was inevitable; we really wanted to have control over the way we did things and not be beholden to bigger companies and the biggest industry institutions, so we had to become bigger.

Part of me thinks this is about insecurity; that we as independents feel the need to get bigger so we’re not ‘small’!

There’s that saying: if you’re not growing, you’re dying. But then I think it was [PIAS] who talked about the analogy between the independent music industry and the craft beer analogy, which is great.

While we decided to become bigger, I also believe there’s an important role for smaller companies.

They’re the best at creating things that aren’t necessarily geared towards mass consumption – and that’s really important. They have a cultural impact locally, and if, from time to time, they also have an international impact, great, but that’s not their original or prime motivation. There’s something inspiring about that.

And the bigger you become, it’s harder to create on that level. So you do lose something. I think about all those music companies out there who decide intentionally: ‘We’re going to stay small.’ We should support them and make sure that our ecosystem doesn’t require that they choose between becoming bigger or dying.

What’s your purpose? Why do you do this?

Maybe I have a chip on my shoulder! Why did you start [PIAS]?

Sorry, no… you can interview me later. I ask the questions!

It took me a while when I was younger to find what it was that motivated me. Early on in my life I worked out that I always wanted to produce things and create things. Getting a math degree wasn’t exciting to me, because I had a hard time connecting that education to what I was going to produce.

But being in the music industry — supporting artists and seeing them play bigger and bigger shows, releasing CDs and being part of something with a more immediate impact — that was more inspiring to me. It made me feel like I could make a difference in this world.

‘I could make a difference in this world.’ That sounds like the purpose!

Absolutely. That is why we kept building what we created.

It has never been about building a statue of ourselves. It has always been about trying to make the world better in some way.

[video_youtube id=”ccLW2Jb_lJM”]

Emotions are important in our business.

Yes. They’re the reason we sometimes make un-business-like decisions that end up being the reason why we succeed.

There are times when all of us as independent labels have met an artist and thought, ‘I have no idea how to market their music and the recording fund they need to make this album is crazy. But we have to make it work somehow, because it’s something we really believe in.’

Then you’re a part of helping create something that is unlike anything else in the world, and occasionally you also have the good luck of having great success from it.

Do you look at some people as being your mentors in the music business? People who inspired you?

Yes, of course. On the label side, when we were starting the distribution company, we really looked up to Touch & Go and how Corey Rusk created a wonderful community of labels, and we loved how they did things – they relied on handshake deals, 50/50 with their artists, and there was a real sense of honor and partnership.

There are many other people who ran labels we found inspiring, like Dan Koretzky of Drag City or Ian MacKaye of Dischord. And artists are always inspiring us – Justin Vernon, for example, is a friend but also a mentor as far as how he approaches his community and really inspires artists around him to take it up a level.

And when it comes to trying to get our whole community of independent labels to work for a better ecosystem or a more level playing field, I look up to people like Alison Wenham and Martin Mills. I’ve had the good fortune of working with a lot of inspiring people to guide us to where we are now.

[video_youtube id=”6C5sB6AqJkM”]

Your company is 20 years old – are you going to celebrate it?

I don’t know. I hate anniversaries. Even in my personal life, I hate birthdays, anniversaries and all that stuff.

We will have some sort of special anniversary celebration – but for me it’s a little bit awkward to stand around a cake clapping. But I suppose if there’s an excuse to have a party, you should have a party.

What’s your proudest moment over the past 20 years?

What’s your proudest moment over the past 20 years?

We started a group of companies that now have close to 100 employees. We are growing, and we have employees and artists growing with us. We have many artists who can now earn a living just from their music.

I think up until this point when we had a sustainable business, for us and for the artists we work with, there was a lot of insecurity.

But now, being part of this company with some strong partners, being able to create something that’s making the world a better place while staying true to our ideals in terms of transparency, and having relationships that go on for 10+ records in some cases – these continuing relationships – I’m very proud of all of that.

Did you have some dark moments along the way? Going from 4 employees to 100 you must have had some growth crisis moments? “I’m fucking it all up!”

Yes! None of us went to business school, none of us were trained to be managers. We’ve had all levels of depression, highs and lows. But there’s that saying: ‘If you’re not fucking up, you’re not trying hard enough.’

We genuinely have moments of self-doubt when things are all going well: ‘Are we not trying hard enough?’

I believe that what makes most people in business so successful is a constant level of self-doubt.

You’re always chasing something. Then maybe later in life you come around to thinking: ‘Maybe I can stop chasing, and just be.’

Have you made many mistakes?

We’ve made every mistake. Then again, if you don’t make mistakes you don’t become better. Successful companies are those who learn from their mistakes.

So for the future of the Secretly Group, what’s the ultimate goal? What’s the next step?

We want to continue starting relationships with artists that are inspiring to us. What’s the next level of that? I’m not sure.

There’s a lot of things that are changing right now in the music industry – some are good and some are bad. One thing we see is more of an emphasis on music that gets listened to repetitively.

The streaming economy rewards music that is catchier and gets repeated listening much more than the older sales-based music economy.

So one challenge we now have: how can we continue to release artistically challenging, progressive music by groundbreaking artists while maintaining our marketing expertise, our staffing and more, when so much of what we’re earning is now coming from streaming services?

What does a world made out of 90% streaming look like for Secretly? Is it scary or exciting?

What does a world made out of 90% streaming look like for Secretly? Is it scary or exciting?

It’s the market. Independents are probably better suited to dealing with a changing market than the majors because a lot of us are willing to just blow it up and start over again.

We never get mad at what the market is. If you spend a lot of energy trying to not let the market be what it is – long term that’s wasted energy.

Does streaming today favour major labels?

I’m not sure whether that is the case, but I often worry that it does. We’re told in the first half of 2016 that the US market grew 8% by the RIAA, largely due to streaming blowing up and growing at a significant rate.

That growth rate is being felt at the top of the food chain. But do we know how much of the streaming service growth is with top of the charts artists – pop repertoire – compared to independent repertoire?

Do we have visibility on what parts of our industry are growing and what parts are shrinking?

That’s a challenge for the independent trade organisations – to really get a perspective on how independent companies of all sizes are dealing with the new streaming paradigm.

What does it mean if the new four-person independent company can’t sustain itself, if the industry as a whole is growing at a significant rate, but they are not? What does that mean for culture? What does that mean for artists who need small labels to develop their voice?

And if streaming does indeed favor major labels, I worry about what that would mean for the diversity of the music marketplace in a few ways. Does streaming make it harder for local German repertoire to gain headway in the German marketplace? Does mainstream US or British repertoire have a greater cultural impact than it should in some parts of the world?

You’ve opened a pressing plant – maybe vinyl is the answer!

Yes, but only to an extent. There’s a reason why smart business people who ran major music companies in the past divested their manufacturing plants.

It’s been a crazy adventure – we’re now turning the corner to profitability, but there’s been lots of crazy stories about $2,000 specialist screws, or a gas pipe half a mile away from the plant having a crack and pressure going down as a result, meaning our boiler couldn’t run for a few days. Disasters you couldn’t dream up happen all the time!

Are labels still worthwhile for artists?

Yes but maybe we’re now at a time when we should stop thinking about or defining things as strictly ‘artist’ vs ‘label’. As the music industry continues to evolve it’s more interesting to think about functions.

If you’re an artist and you’re releasing music, there are certain functions you need taken care of. You need help marketing your records, and you need help financing and distributing them – as well as management of your live shows etc.

All of it contributes to an artist’s music business. I see the future of being a label as being a flexible company maybe providing services, maybe providing management, maybe providing finance – directly or non-directly. We’ll slowly get to a place where we stop thinking rigidly about who is the artist and who is the label.

The War On Drugs: you had huge success but lost them to Warner. Does that hurt?

The War On Drugs: you had huge success but lost them to Warner. Does that hurt?

The competitive side of us says yes. We would love for them to have stayed. Adam is a brilliant artist with a brilliant band, so of course we’d love to continue to work with them. But we lost out and we’ve accepted it.

Part of what happens when an artist leaves for a bigger company is that it hurts but it reminds you that you still have more to do – to be in a position where, the next time that conversation comes up, you can make a stronger case that they should stay with you.

Don’t you want to tell them to f*ck off at some stage? We’ve seen it a million times – they take the money at a major then come back two albums down the line begging to be taken back!

[Laughs] I do believe that long-term, when you compare what we were able to offer to their new agreement they might see we were a more attractive proposition.

But sometimes artists want to be with a company they feel can deliver commercial radio – and that’s one part of the music business that’s not yet a level playing field between majors and indies.

Why would an artist sign to Secretly Group?

Of the independent companies, we’re one that can release your record internationally, and we have amongst the highest batting averages when it comes to introducing new artists to the world and being successful.

Our proposition: you can be who you are as an artist, we’ll scale up to your ambition, we’ll be patient with you, we’ll be your partner, we’ll be ready when you want to achieve a high level of [commercial] success but if you’re the kind of artist who is still making beautiful music but only selling at a certain level we can be that kind of company for you as well.

As far as signing with any independent, the analogy is: we’re like farmers who actually have an understanding of what soil will give the seeds the best chance of growing into something beautiful.

I like that analogy. Do you care about market share?

Collectively as independent companies across the industry, yes – we need to know our collective clout when it comes to negotiating with the big digital services. But as an individual company, no.

Why are the majors so obsessed with it?

Because their over-head is not sustainable. Increasing their market share gives them an added opportunity to leverage their scale, so they can defend their old, crumbling castles.

If they can achieve a market share that allows them to dictate terms, grab that extra 2% or 3% – that extra bit can help support a lot of big salaries at the top of those companies.

Some of the people at the top of those businesses are good people, and others are doing what they’re supposed to do – delivering the best returns for their shareholders. There’s immense pressure in these companies to figure out ways to get a little bit more here or there.

[video_youtube id=”pWDvlekoPkg”]

Why did Sony buy Essential?

I don’t know why. And I don’t know why Sony invested in The Orchard either. If I am being generous, maybe it comes down to scale advantage – and I don’t have a problem with that if it’s about combining accounting departments or consolidating management or things like that to reduce costs. But it’s the potential abuse of scale advantage that worries me.

If I am being less generous, maybe when a company like Sony is buying The Orchard or Essential, they are looking at their bottom line and saying: ‘Hey, in this country there’s $X of revenue happening , so if we increase our market share by buying this company or that company, we can get closer to cornering the market, which means there will be less competition and more control and profits for us.’

If this is what is actually driving acquisition, then that is a big problem for all of us. Because when the music marketplace becomes less competitive, all of a sudden we end up with a business environment where the biggest companies can artificially hike prices and fees, and where music releases become more homogenized.

Smaller companies and newer forms of music can’t compete, consumers suffer, and culture is negatively impacted. All bad things.

Are you a romantic?

Yes. How can you not be romantic in the music industry! You’d be working at Google if you weren’t.