Chris Wright is a founding father of the independent music business – one who last week found himself back in the headlines.

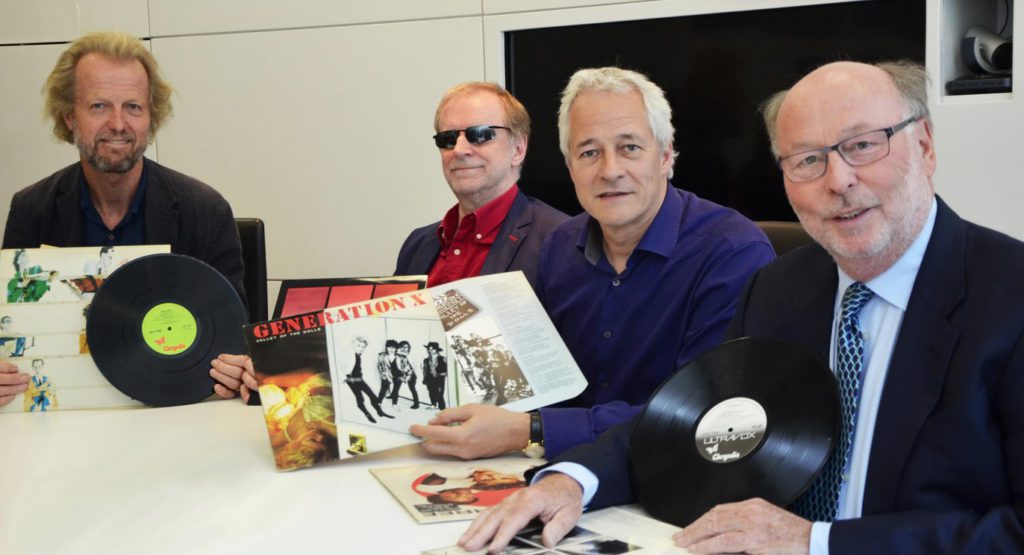

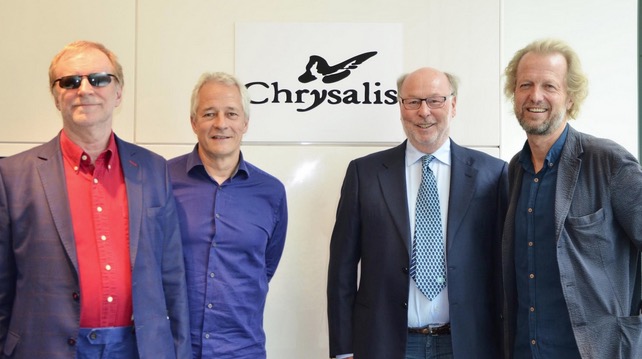

As part of an independent group at Blue Raincoat Music, Wright and the likes of Jeremy Lascelles have bought back the Chrysalis Records catalogue from Warner Music Group.

Alongside Terry Ellis, Wright founded the Ellis-Wright music agency in London in 1967 – changing its name to Chrysalis a year later.

The duo forged a legendary A&R reputation across both publishing and records, standing toe-to-toe with the likes of Richard Branson’s Virgin and Chris Blackwell’s Island Records.

Chrysalis Records’ first signing – Jethro Tull – was a hit, but the label would go on to earn a sterling A&R reputation with a roster that included the likes of Blondie, Procol Harum, Ten Years After, Billy Idol, Huey Lewis, Sinead O’Connor and Spandau Ballet.

It wasn’t just music in which Chrysalis thrived, either: the company later launched books, radio and TV enterprises to notable success.

However, in 1991, 24 years after it was founded, Chrysalis Records was sold to a major – EMI – for around $100m in total plus debt.

Wright admits today that he had little choice: the company was struggling to make money in the rapidly-changing nineties marketplace.

In 2010, Chrysalis’s publishing company went too: BMG swooped for Chrysalis Music in a deal believed to be worth $168m, bringing Wright inside the Bertelsmann subsidiary in a hands-off role.

Below, [PIAS]’s Kenny Gates grills Wright on the highs and lows of his 30+ years with Chrysalis, his approach to artists – and about his plans with Blue Raincoat…

You are one of the first ‘faces’ of independent music. But who were your mentors?

You are one of the first ‘faces’ of independent music. But who were your mentors?

My mentors were people who really got on with artists – who could communicate with them but also be successful.

You could list people like Jerry Moss, who I get on well with, but I’m not sure if he was a mentor, exactly. Mo Ostin was also very, very good.

[Led Zeppelin manager] Peter Grant (pictured) and I were pretty close.

He started off as a stunt double for Robert Morley – a big English actor – before becoming a road manager, employed by people like Don Arden, and eventually managing Led Zeppelin. Then it kind of all went off the rails for him.

Peter taught me a lot about everything in the music business, although he didn’t teach me how to run a record company. We shared the same building the West End in the early years – he was on the top floor, I was on the first floor.

So the music industry was a bit of a dirty place back then?

It was a gangster business until the late sixties and early seventies. The stories you hear about Don Arden were all true.

In the States, you had Warner-Reprise, which was started by Frank Sinatra, with Mo Ostin running it.

A company called Kinney bought it, and also bought Atlantic and Elektra. They changed the ‘Kinney’ name in music to WEA [Warner-Elektra-Atlantic].

You don’t need me to tell you the kind of corporation Kinney was if I told you it was run by a lot of Italians and owned car-parking and funeral operations in New York City.

Were you and Terry scared of this environment?

We weren’t, because 21-year-old kids aren’t scared. But we knew what was going on. You couldn’t just open a club in the middle of London and expect to do well without getting a visit from a certain group of people.

The Kray family had an agency, called the Charles-Kray Agency, which represented some important groups. We were one of the first people to be successful in the music agency/management business that didn’t have a hard edge to us.

Before you set up the record company, who were your clients?

Before you set up the record company, who were your clients?

I was managing Ten Years After, Blodwyn Pig and Procol Harum (pictured). I sometimes made two gigs in one night – including a plane flight. If I could see an early Ten Years After gig in New York, then fly to Detroit or Chicago, and [benefit] from a one hour time change, I would do it.

I nearly died from nicotine poisoning – I was sleeping about three hours a day and smoking about 80 cigarettes a day.

Is it true that money is not your motivation?

Correct. I never did anything for the money.

The way to be successful is to get up in the morning and do what you do without thinking you’re getting paid for it.

My philosophy is that if you do things you love without focusing on money, then money comes to you…

Exactly. That’s not just true in our business, but in life in general.

Anybody who starts thinking: ‘That’s a great idea, I can make some money,’ I don’t think they’re ultimately going to be that successful.

What are the high points and low points of your career?

What are the high points and low points of your career?

The high points: in the late ‘60s early ‘70s managing Jethro Tull, Procol Harum, Ten Years After and so forth, and how big they became – playing arenas and stadiums.

Starting the record company and being successful was a high point. And then with Blondie (pictured), we made the record company successful on both sides of the Atlantic – same story with [US signings] Huey Lewis and Billy Idol.

The low points: the last days in partnership with Terry were tough. When the record company was running out of money and we ended up having to sell it to EMI, that was very tough.

So it wasn’t a choice to sell to EMI?

No. We’d run out of money.

Essentially, we were losing too much money in America. We could have vacated the US, and in retrospect perhaps we should.

If we’ve retrenched to England, it could have been a very different scenario.

What about selling the publishing business to BMG? Why did you do that? Do you regret it?

What about selling the publishing business to BMG? Why did you do that? Do you regret it?

You know, you can regret a lot of things – and there are a lot of things I would have done different in retrospect. But you’ve always got to look forward, not backwards.

In terms of selling to BMG, I was stuck. We were a public company and we’d sold the radio stations in 2007. The value of the publishing assets was quite considerable, and I only owned 30% of the overall business.

I had shareholders that bought the shares and manipulated the situation to force the sale of the company; they knew they could double or triple their money by buying cheap and forcing a disposal.

Having said that, we’d seen multiples [of the company’s value] drop from the high teens to single figures as downloading took over from CD.

We tried everything possible that would satisfy the shareholders to keep the company alive.

We had so many deals that could have worked: merging with Bug was one, because they were well financed. That one very nearly happened – three times we went down the aisle, and when we got to the altar, they didn’t have the ring!

So why BMG?

The thing with BMG, why they’ve been successful, is that they’ve always said: ‘We necessarily don’t pay the most, but you’ll get your money.’ They have a really good infrastructure for mergers and acquisitions.

If there’s a company that can be bought, BMG will throw more resource at getting the due diligence done, and getting the deal done, than many other people.

When you get to the altar, they have the ring. It may not be the brightest ring in the jewelry shop, but it’s in the pocket – ready to go on your finger.

How’s your relationship with them now?

I always had a good relationship with BMG, but now I have no relationship with them. I have nothing against them; they bought the company, there was an arrangement, it lasted and then it came to an end. That was it.

When I arrived at BMG, Thomas Rabe was responsible for it. Two or three years ago, the guy who was running Bertelsmann got moved aside, and they promoted Thomas to run the whole thing.

I must say Thomas Rabe is probably the most impressive executive I’ve ever worked with.

Do you see yourself as an A&R man, a businessman or a serial entrepreneur?

Let’s go through them one-by-one.

A&R: That’s what I used to be. I would not really be that effective as an A&R man now, although maybe I could be in a certain genre of music.

I love listening to the music that I love listening to – but I wouldn’t be effective in pop, hip-hop or anything like that.

In the 1970s and 1980s, they’d always say that Richard Branson was a businessman pretending to be a record man, and I was a record man pretending to be a businessman!

I don’t think I’m a great businessman, but I’m a very good organizer. For example, I recently took over running the Nordoff Robbins charity race day after Willy Robertson.

It always made £25,000 for the charity. The first year I took it over it made £50,000, then the next year it made £75,000, then £100,000, then over £100,000 – and this year it made over £150,000.

I’m very good at building something up brick-by-brick. And I’m good at communicating with artists and understanding talent.

A serial entrepreneur?

No, I don’t think I am that one really.

Come on! You’ve done records, publishing, TV, radio…

Okay – I guess you must be right!

Which out of those is closest to your heart?

I enjoyed the TV business, but the closest to my heart is the music by far.

I wasn’t that keen on the radio business – it’s not creative.

In the radio business, we used to pay people a lot of money to programme the station. About 50 housewives would turn up on a Monday night; the [executives] would play the records to them and let them choose what they like.

It was stupid. I thought: Why am I paying these people £100,000 a year to decide what to play on the radio, and all they’re doing is asking these housewives?

And then I’d say, ‘Why aren’t we playing this record?’ And they’d say: ‘Because it doesn’t test well.’

That’s the radio business.

Isn’t the music business a bit like that now?

Probably. And the film business – it’s the same thing. They shoot three different endings and play them to focus groups to pick the best one.

Is the buyback of Chrysalis Records an emotional move for you?

Is the buyback of Chrysalis Records an emotional move for you?

Well yes, of course. Our plan is to run it as as an independent, revitalising the catalogue for the digital age.

When I sold the first half of the Chrysalis label to EMI, I fought very hard to put a clause in the contract that every single artist on the Chrysalis label had to stay on the Chrysalis label; it could not be decimated. That’s why we sold to EMI – because they agreed.

That clause is still in the contact and still fully enforceable, and the Chrysalis label should never have been fractured like it has been [since UMG bought EMI Music and then sold Parlophone assets to WMG in Europe – so UMG still owns the Chrysalis US recordings].

When you started in 1969, was there a community of independents?

Yes. The business then revolved around the majors, who I suppose were EMI, Decca and CBS. Other smaller companies like PIE were still ‘major’, and it was the same for Phonogram and Polydor.

Really, the original independent labels would have been Island and Sonnet in Sweden, plus you had Festival in Australia.

Then it soon developed – Chrysalis became a proper record company, then Virgin a bit later and Charisma with Tony Stratton-Smith.

There was this feeling that innovative and interesting music back then belonged on independents.

In reaction, the majors started their own ‘indie’ imprints; Decca started Deram and EMI relaunched the old Regal Zonophone label – they were pretending they had an independent vibe, but it just wasn’t the same.

Nothing changes! Was there a feeling that the independents were the good guys – that the majors were corporate bad guys, and that you were the underdogs?

Yes, yes and yes. It still remains the same!

Running a company is lonely: ‘I’m going to go bankrupt, I’m shit, I’m going to lose it all.’ Did you have those feelings and how did you deal with them?

I’m not sure I ever felt that doomsday scenario, but it was always difficult.

When you’re an independent, nothing comes easy. Nothing gets delivered to you.

If you’re running Warner in London and one of the acts signed to Warner in Chicago or New York, you get it handed to you.

As an independent, everything has to be created yourself, and it’s all your money. There’s never complete security.

Every time you have a successful artist, you know there are majors sniping to get your artists. We even see that now, with Adele going to Sony.

The minute an independent has a successful artist, the majors think: ‘Oh it’s only an independent, we can steal them.’

It’s the same with people: you give a guy a job as a young scout, he signs a group that’s successful and all the majors try and nick him.

In my entire time in the business, it’s very rare to think of any artist who has really benefitted from switching labels – especially from an independent to a major. And I’ve seen a long history of it.

Did you lose any artists in that way?

Did you lose any artists in that way?

I think we kept all of our artists – but we had to stay very close to them and be very supportive of them. I think it’s amazing we did that.

The only artist we didn’t keep was Spandau Ballet. I think we did a fantastic job on them, but we didn’t in America.

When Terry was running the American company and I was running the company outside America, it was difficult to get the [US team] to work on UK-signed artists.

The Spandau Ballet album with True and Gold on it sold almost as many copies in Canada as it did in America – around 450,000.

It’s clear the American company didn’t do as good a job as it could have done, and we had to let them leave.

Any acts you tried hard to sign and failed that you regret?

We could have signed The Small Faces, who later became the Faces with Rod Stewart. But that was because Alvin Lee wasn’t very keen on us signing them.

We didn’t sign Dire Straits, but we turned them down. And David Bowie was signed to our publishing company but we didn’t sign him to the record company because Terry didn’t like the Hunky Dory album. You can’t sign everybody!

The Specials and Spandau Ballet and Generation X were all very competitive deals, and we managed to get them all – beating the majors.

You hired Daniel Glass at Chrysalis, right?

You hired Daniel Glass at Chrysalis, right?

Yes, and Simon Fuller (pictured), and Jeff Aldrich and Ron Fair and Pete Edge and Guy Moot. They all started at Chrysalis – it was the best training ground.

Why?

I don’t know. But what’s that old Chinese proverb? If the student turns out to be better than the teacher then it’s the biggest success of all.

What do you make of the leaders of the record business these days – Lucian Grainge or Doug Morris?

I always thought a lot of Lucian as an executive. You don’t achieve what he’s achieved without being very good.

I don’t know Doug Morris so I can’t really comment on him.

But I do think that there are people in the music business that are a little like the striker who’s struggling to score goals but keeps wanting to play for the team. You do lose your effectiveness after a while.

What’s your view on streaming?

I think it’s fantastic. The great thing about streaming is you can play any obscure record you want and have it delivered instantly with great sound. It’s incredibly user-friendly.

When we went from 12-inches to CDs, something was lost. Then going from CD to download was the next stage of getting nothing. So when you’ve got nothing, you may as well turn to streaming!

One of the reasons I think vinyl is doing so well is so people can have something to look at.

We used to spend as much time making the sleeve and packaging, in a way, that the groups spent making the music!

Is there one song that stands out for you ever written?

That’s very hard. I do think Paul Simon is probably the most talented person who has ever existed in our business. One song, though, that’s impossible.

Are you a hopeless romantic?

Yes.

Can you explain why?

No!