For a decade between the mid-Seventies and mid-Eighties, Stiff Records changed everything.

For a decade between the mid-Seventies and mid-Eighties, Stiff Records changed everything.

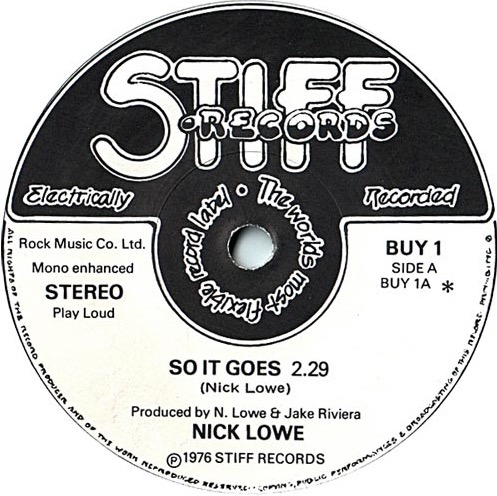

Its first single was a stone cold classic: Nick Lowe’s So It Goes, released on August 14, 1976 – and voted in the Top 5 singles of that year by NME.

By single three, Stiff was shifting the axis of counter-culture: The Damned’s New Rose, released on October 22 later the same year, is widely regarded as the first ever UK punk single. (It would be another month before Malcom McLaren’s The Sex Pistols released Anarchy In The UK.)

Stiff started as a proudly ramshackle indie, created out of thin air – and personal bank accounts – by Dave Robinson and Jake Riviera.

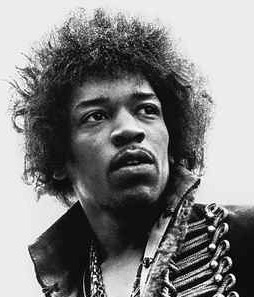

Robinson was a well-known artist manager looking after the likes of Graham Parker and Ian Dury who had spent time as tour manager for Jimi Hendrix. Riviera had tour managed much-loved British pub rock act Dr Feelgood.

They didn’t exactly know how to run a record label – but they firmly believed they could do it with more panache, and treat artists more fairly, than the big record companies of the day.

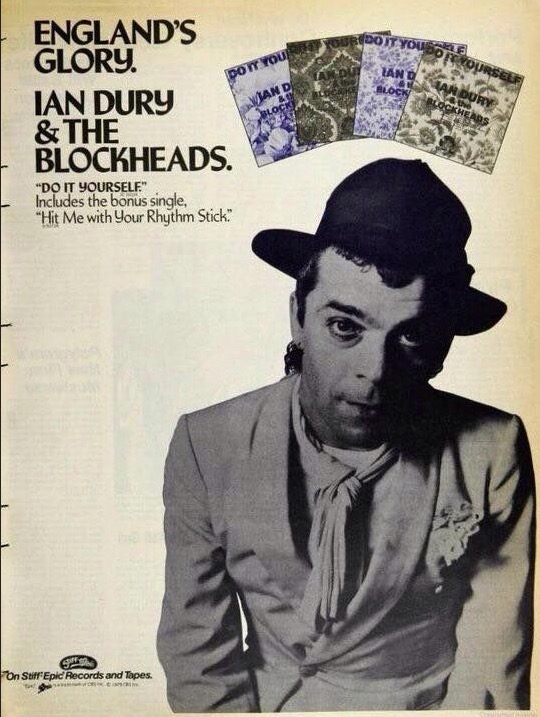

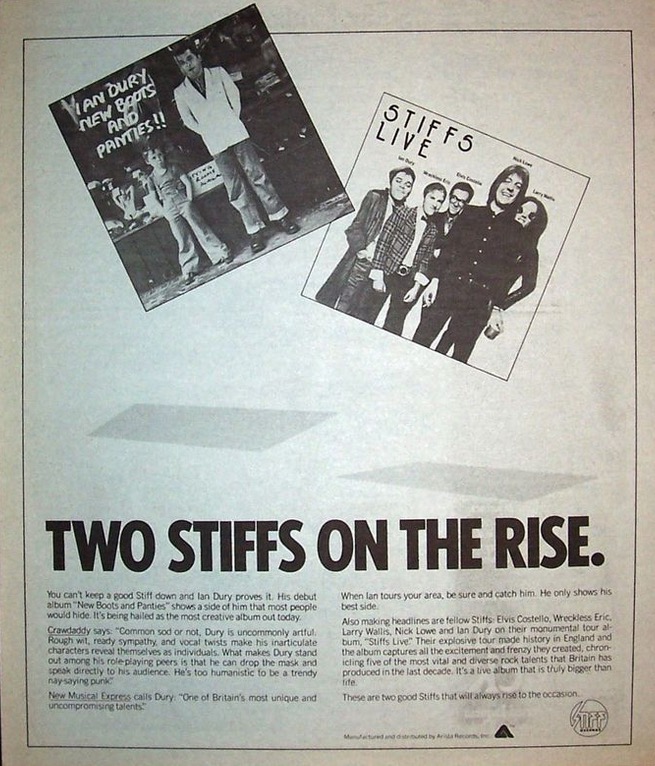

In the ten short years in which Stiff was active, it broke titans of the British music scene from Madness to Elvis Costello and Ian Dury.

It also gained a reputation for its irreverent, two-fingers-up aesthetic, epitomized by a run of press ads which, for the music biz establishment of the time, required a strong drink and a sit down. (‘If it ain’t Stiff, it ain’t worth a fuck,’ was one memorable entry.)

Along the way, Stiff became one of the most influential independent labels in history.

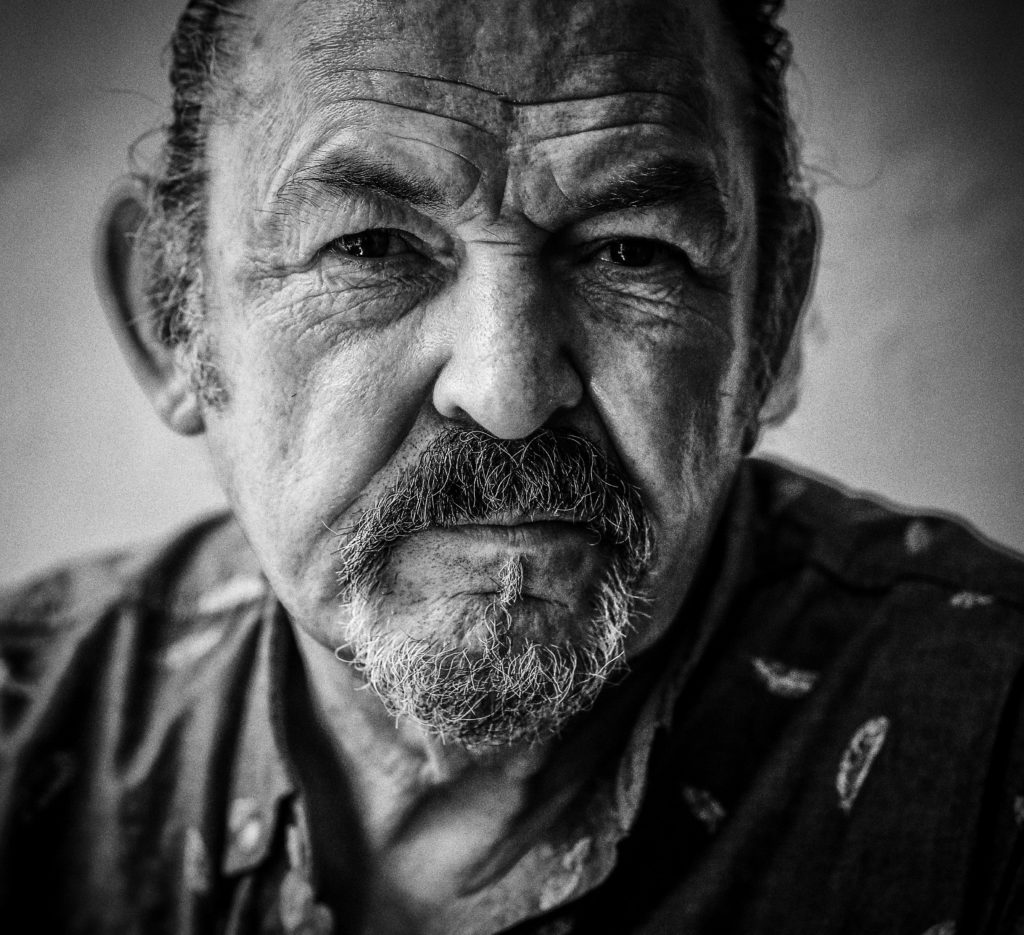

[PIAS]’s Kenny Gates sat down with Dave Robinson (pictured inset) to get a personal history of the label’s rise – and its ultimate decline – before it was sold off to ZTT Records in the late Eighties…

What made you start a label?

What made you start a label?

I was managing quite a few people: Ian Dury, eventually Elvis Costello, Graham Parker. I’d signed several bands to quite a lot of different labels: EMI, Phonogram and others.

For Graham Parker in America, the licensee was Mercury Records. You always think when you sign to a record label they’re going to know what to do; that they’re going to step you up and put you straight in the charts and that people at the labels are going to give you really good advice.

I realized, eventually, that the labels actually knew very little. Their whole attitude was pretty much to get the band to tour, and they had one advertising slogan for every artist: ‘Out now.’ That seemed to be all they were about.

“I realized, eventually, that the labels actually knew very little.”

Nigel Grainge was the guy who signed Graham Parker to Phonogram; Nigel was very enthusiastic. He got you going and got you thinking things were going to be a success.

But then you’d talk to the marketing department and the budgeting department. Graham was very big on the east coast of America to start; he was ahead of Bruce Springsteen. Bruce was at the gigs, looking at him and, it turns out, worrying about him.

But Mercury had no attitude, no marketing, they weren’t even taking any ads at radio stations; the stuff you have to do to promote your band. They were very poor at it.

As a result, Graham Parker wrote a song called ‘Mercury Poisoning’, which obviously didn’t do anything for our relationship with Mercury, but was thoroughly accurate.

So you decided to do it yourself?

Exactly. My whole life has been bound to the phrase: ‘How difficult can this be?’

In England I met up with Jake Riviera, who’s been managing a couple of pop bands and had been to America with Dr. Feelgood.

He was very keen on the idea of an independent label. I had quite a lot of tapes of bands I’d recorded live at the Hope & Anchor pub to get us started.

Jake was managing Nick Lowe, who I had managed earlier and thought was quite a clever songwriter and possible producer. So we formed together, with very little money, to start Stiff Records as a hobby.

Why is attitude important at a record label?

Why is attitude important at a record label?

I talked to a few people like Seymour Stein, who I met during this period, and I started realizing that the major labels [in London] were essentially distributors and manufacturers, and the independent labels in America were the people who found the artists, made the hits, and then couldn’t cope so had to get distribution… from the majors.

The only reason the majors had their own A&R departments is that they found the independents were a bit seasonal. So there’d be periods when the factories wouldn’t be manufacturing – that the distributor wasn’t having product put through there.

That meant major label A&R was always based around the bottom line; the creative element of it was incidental. They were selling plastic, and the music was just an extra marketing aid.

“The majors seemed very exploitative. Stiff was born out of that.”

I was very devoted to the idea of bands writing songs, having hits and the public going mental about it. It was about music getting people together.

I wanted to see if it was possible to run a [record label] on that philosophy. I was also very influenced by Chris Blackwell’s Island; he had an agency, a management company, a publishing company and a record company.

With the big margin he was getting from his groups, he was able to invest more in his bands and give them direction, but also tour support and practical things.

[The majors] assumed that for some magical reason this little band traveling in a van up and down the motorway would just be able to support itself. It seemed very exploitative. Stiff was born out of that.

So Stiff was born out of a hope to treat artists more fairly?

Yes. The job of a record company is to be a partner to the musician.

There is income for both of them, a win-win. Or there is a break even – a situation where if you care for your band, they’ll at least be able to make some kind of living.

We were very creative as a label simply because we had to attract attention to your band.

You would have an unknown group from Liverpool or Manchester, Holland or wherever. And you had to single-handedly attract the media to support you, who in turn would attract the public to buy the records.

Does being Irish make a difference to your tenacity? I interviewed Alan McGee recently and it was clear that being Scottish helped make him who he is.

Does being Irish make a difference to your tenacity? I interviewed Alan McGee recently and it was clear that being Scottish helped make him who he is.

It probably does. To be an immigrant in the marketplace is a help.

The thing about the Celts is basically we’re anarchists. We oppose the status quo. And that was good from an independent record company point of view.

You constantly questioned how things were done.

Stiff became famous for our ads; the major record companies would have their marketing meetings on a Tuesday. I had a lot of moles in a lot of record companies, and I used to enjoy that these marketing meetings used to be taken up by someone arguing about what Stiff was doing. We were getting in their hair!

Alan is very similar to me in a lot of ways; we meet from time to time.

“The thing about the Celts is basically we’re anarchists.”

Stiff were the first label perhaps outside of Virgin which, to my mind, did some ‘brand marketing’ – making the public aware of who you were as a label. You did that through proverbs and phrases in your marketing.

It was a reaction against the major labels. As you know, a ‘stiff’ record meant a record that wasn’t a success. We came up with loads of slogans like: ‘If it means everything to everyone it must be a Stiff’.

I took an ad when we were distributed by EMI which said: ‘Stock now while EMI lasts!’ I got a letter from the chairman of EMI complaining about it.

There were five music [publications] who needed stories and they needed interesting ads. Because all the other ads just said, ‘Out now’ we stood out because we cared and we were prepared to put our money where our mouth was.

Is it true you started Stiff with a £400 loan from a member of Dr. Feelgood?

Yes but in actual fact we never spent that money. That’s part of the legend. That cheque was framed on our office wall. We never cashed it.

The money that started Stiff was actually the income from the management company. It was a hobby, so the first 10 records we had from tapes we already had.

The very first single was a track Nick Lowe had done in a couple of hours at a small studio – So It Goes. I think the studio was £8 an hour.

John Peel was another very important ingredient.

He was prepared to play stuff nobody else would. I knew him from all the festivals. I sent John our first couple of singles, and to my amazement he played them – and he played them enough that Seymour Stein heard it, and said: ‘What is this and can I have a bit of it?’

Is it right you were involved with Jimi Hendrix?

Is it right you were involved with Jimi Hendrix?

Yes, I was his road manager, and when the Tour Manager got ill I became his Tour Manager, as a very young, naive Irish boy just off the boat in 1967.

I had nearly two years with Jimi. He was a great example of how not to manage someone brilliant – his management was appalling in my view.

I couldn’t understand why he was on the road all the time. Nobody from the record company came out to his shows.

Jimi was a very nice guy – not very bright, but a great guitar player who was very badly managed and handled by everybody.

I was curious about how incredibly bad management was able to survive while just making use of these musicians, who weren’t clever enough to get control.

The lawyers worked for the big companies, the managers had the relationships with the big companies – everybody seemed to be taking away from the musicians.

Was that your philosophy at Stiff – to be guardian angels of musicians?

Yes. Stiff’s ethos was to try and look after the musician – to try and advise them.

Musicians were being exploited generally, and they weren’t thinking of the future – taking a lot of drugs while seeming to have a great time.

People cozy up to me nowadays and say: Tell me about the Jimi Hendrix days! They want the salacious stories. They really don’t want to know about the fact that he died with $5,000 in his bank account.

Tell me about your upbringing. What were your parents like?

My parents didn’t really get along.

I went to boarding school when I was four, and I was there until I was about 16 – at which point I’d had enough of the religious teachers.

If you survived boarding school in Ireland you were doing pretty good. And when I was 17 I got a job in England as a photographer, so I left.

Was New Rose by The Damned really the very first punk single?

Yes. We discovered them at a festival in France. Malcolm McLaren and The Sex Pistols were starting to go but Stiff was always the quickest.

We always tried to be quicker, smarter and stay up later than everybody else.

Is Stiff a punk label?

We had a lot of punk bands, and people thought the name was ‘punk’.

The Americans came up with the name ‘new wave’ – they thought The Police and Elvis Costello were ‘new wave’.

They couldn’t understand the early punk thing, which was very British in its outlook.

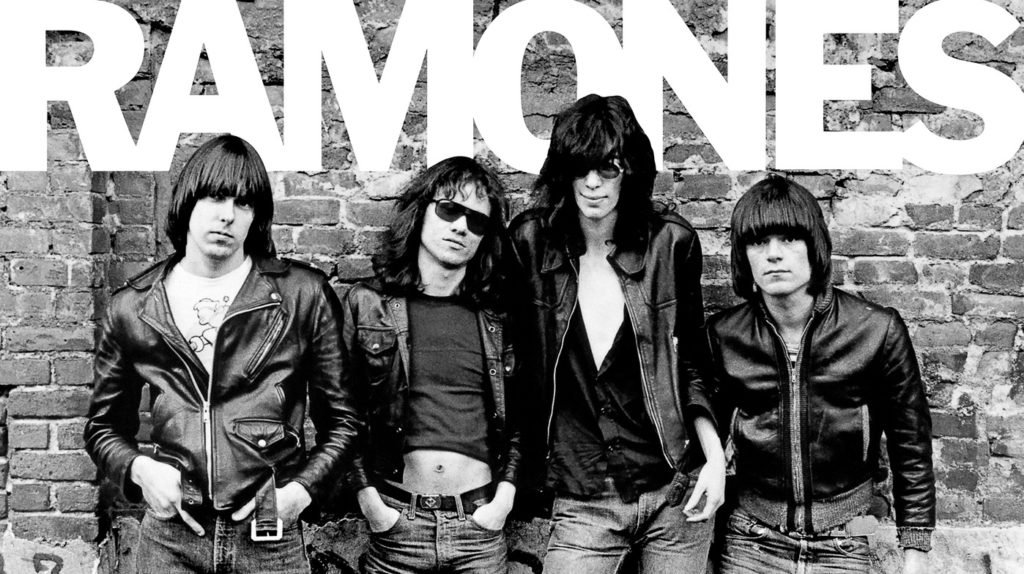

Well they had The Ramones.

Well they had The Ramones.

The Ramones were good, but they were very well-washed. They came to London and people spat at them at their gig – they could not believe it.

I was at that gig in Dingwalls. The Ramones came on and they were all wearing lovely leather jackets and their hair was absolutely immaculate. They looked great, the jeans, the guitars… then 400 London punks spat at them.

They were covered in goo. They jumped off the stage and tried to kill half the audience. They could have been done for murder, but the crush was so intense, they couldn’t raise their guitars to bash people.

It was the most exciting thing I think I’ve ever seen.

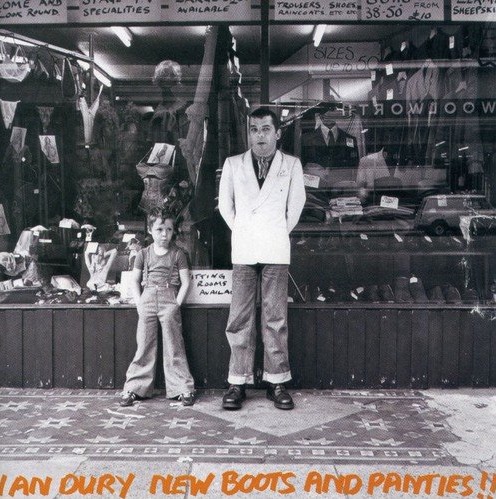

Was Ian Dury a genius?

Was Ian Dury a genius?

He was an amazing guy. I looked after him for a number of years, which really just involved giving him money. He had an attitude. He had a very difficult life.

I eventually traded in the agreement I had with him with Blackhill Music, who used to manage Pink Floyd – run by Andrew King, who now runs a publishing company for Mute, and his partner Peter Jenner.

Blackhill did a very good publishing deal, they were very generous to him and gave him a weekly income, as well as sponsoring his music.

Ian was very opinionated, about art, about everything. He was a pain in the arse a lot of the time, but I had a great affection for him.

“Ian was very opinionated, about art, about everything.”

New Boots And Panties is one of the great British albums. Peter Jenner had a lot of contacts at EMI. I heard the album in the [Stiff] office and he said: ‘This is not for you Dave – this is for EMI.’

I was amused because I had pitched the same [artist] to them two years before when I was managing him. Blackhill took a 33-year-old cripple who couldn’t sing down to EMI and asked them to sign him!

EMI were incapable of seeing the beauty of that music! They were into glam rock, platform shoes, all kinds of rubbish. They weren’t discerning.

EMI passed, so did every other major in town; and eventually, [Jenner] had to come to me and say: ‘Will you put it out?’

You sold 50% of Stiff to Island in 1983 – good decision or bad decision?

You sold 50% of Stiff to Island in 1983 – good decision or bad decision?

It was a terrible decision; the biggest mistake of my life.

I had to lend Chris [Blackwell] money to buy my shares. Island was totally broke. That possibility never occurred to me – Island were always a big label in my mind, with 120 employees.

Chris was a friend of mine, we would see each other two or three times a year and go out for dinner. He said: I’ll tell you what I’ll do, I’ll buy half your company for £2m – he set the price – and you’ll run both [Stiff and Island].

I had a chat with my wife, I was over 40, I had children and I thought, why not?

I was a friend of Trevor Horn and I was very aware of Frankie Goes To Hollywood, who had an extraordinary record.

[When I arrived at Island] I got Frankie to Hollywood’s record going – did a few clever moves – and go it into the charts.

A DJ called Mike Reid threw it at the wall on-air, breaking it and calling it obscene.

A BBC guy called me up and said: ‘We’re going to ban this record because it’s all about ejaculation.’

First I told him he should speak to Holly Johnson’s mother, because [Holly] had never had a career, and that he would be shutting it down before it started. When he refused I said you should speak to the press and explain yourself… so he said he would. I couldn’t get off the phone quick enough.

There were 176 people in the press conference, and he told them all that this song they’d been playing for three months and were now banning was all about ejaculation. We couldn’t press enough records after that!

But Island ultimately didn’t work out?

The next thing I know, I’m in a board meeting with Tom Hayes, Chris Blackwell’s General Manager, who tells me Island are broke.

I’m gobsmacked. At that point, I had nothing from the Stiff deal – just paperwork which hadn’t been concluded.

I called Blackwell and told him that he hadn’t said he didn’t have any money when he was telling me how groovy it would all be – that this was all bollocks.

He said no, we’ve got the money and we can do it. To this day, I don’t know why I succumbed to it, but I suppose I like a challenge.

So I went ahead with it. Frankie Goes To Hollywood was doing well. I’d put the running order to Bob Marley’s Legend, U2 were there, as was Stevie Winwood – all people I really related to.

What about Bob Marley’s Legend. How involved were you?

I believed that Island had pushed him very militarily – always dressed in camouflage clothing, and never smiling a great deal in pictures.

So for Legend I came up with the idea we would have a softer Bob Marley, we would take out the political songs, more or less, and just deal with great songwriting.

It’s now at 44m sales.

So in the end what happened with Stiff?

So in the end what happened with Stiff?

I tried to make it into a phoenix label – rising from the flames. But it was too much. Eventually I had to sell it to ZTT to solve the financial problems.

And we had a run-in with your friend, Chris Wright. It was about a band called Furniture, who could have put Stiff back on the front page. What that man doesn’t know about records would fill volumes.

I get along much better with Chris Blackwell still than I do with Chris Wright.

The classic Stiff masters are now owned by a major label. How do you feel about that?

By the time we sold to ZTT, we’d got rid of pretty much all of the key catalogue.

I gave or sold all the Stiff masters to the individual acts.

Elvis Costello got My Aim Is True, The Damned got their stuff, Madness got their catalogue so all that was left was essentially flotsam and jetsam.

Who are your mentors?

I certainly looked up to Chris Blackwell in the formative years of Island. Most of my contemporaries are now dropping like flies!

Seymour Stein was always a great friend, and a guy called Steve Popovich was an influence – one of the great promotion men.

He had a hand in signing Michael Jackson and Bat Out Of Hell.

Why was Stiff proudly such a provocative label?

Music has to provoke; art has to provoke – it’s essential.

Do you need to be a romantic to start an independent label?

Yes. Independent labels are an area where you have to care about your bands and the musicians in them. It’s more of a partnership than a major.

Artists never get to meet the head of major companies, unless they’re having monstrous hits – when he’ll come and be your friend for a while.

At an independent label, you meet the head of the company regularly – and he has to be able to justify how he’s looking after you and your career.

What’s your favourite Irish joke?

A Mormon was seated next to an Irishman on a flight from London to the US.

After the plane took off, the lady came and asked them for drink orders.

The Irishman asked for a whiskey. The Mormon was really uptight – he said: “I’d rather be savagely raped by a dozen whores than let liquor touch my lips.”

The Irishman handed his drink back and said: “Me too, I didn’t know there was a choice.”